Abbreviations

DGBI / DGBIs – Disorders of Gut Brain Interaction(s)

ARFID – Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder

ARFID-S – Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Symptoms

ARFID-ED – Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Eating Disorder

PARDI – Pica, ARFID, Rumination Disorder Interview

ED – Eating Disorder

CP – Chronic Pain

MH – Mental Health

GAD-7 – General Anxiety Disorder

DSM – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

ICD – International Classification of Diseases

CBT – Cognitive behavioural Therapy

ETF – Enteral Tube Feeding

BMI – Body Mass Index

FD – Functional Dyspepsia

IBS – Irritable Bowel Syndrome

CNVS – Chronic Nausea and Vomiting Syndrome

NICE – National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence

Learning Points

- ARFID presentations are common in tertiary care DGBI patients and it is essential to know how to recognise symptoms of ARFID

- The treatment of ARFID symptoms can be the same as the central targeted treatment options for a DGBI

- Trying to separate out an ARFID eating disorder from ARFID symptoms / DGBI can be almost impossible. However, the more severe the ARFID symptoms, the more psychological input will be required and supporting and signposting the patient to appropriate services should form part of the management strategy

Case

21 year old female.

New referral but seen by gastro 2 years prior (extensive work up), tried multiple peripheral acting medications under gastroenterology care (e.g. antispasmodics, peppermint oil, ondansetron, domperidone).

Lost 13% body weight in last 6 months, BMI 17.4kg/m2, still losing weight (1kg in last 1 month).

Multiple DGBIs (FD, IBS, CNVS), GI symptom severity increased since adolescence.

Background of anxiety and depression, current psychosocial impairment (reduced working, not socialising).

Meal and non-meal related symptoms. Pain prevents eating and diet variety and volume is restricted.

So what do you do….?

Introduction

Do they have ARFIDs?

Avoidant (limited variety or avoidance of certain categories of food) and/or restrictive (limited volume or restriction of overall amount) food intake disorder (ARFID) is a new diagnosis in the DSM-5 1 (and the upcoming ICD 112) and is classified as a feeding and eating disorder. The eating and feeding problems associated with ARFIDs are not primarily motivated by behaviours related to body shape or weight concerns (or any other eating disorder (ED)) and instead are thought to consist of three ‘sub-types’ (table 1). In practice there is often an overlap, plus differing severity levels, seen within these subtypes.

Or do they have a severe DGBI?

A debate related to ARFID in DGBI is whether the DGBI led to the ARFID (or vice versa), or if they are both co-morbid, or the same presentation spread along a spectrum of severity3. One major difficulty with understanding this issue is that the main DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ARFID, which is criteria A (table 1), is widely open to clinical interpretation. This leads to both lenient and strict definitions of ARFID with one practical study highlighting that depending on how you define the strictness for criteria A it can double the prevalence of ARFID within an ED population4. An expert working group has attempted to help provide guidance for improved definitions for ARFID diagnosis in research5, however this still leaves the diagnosis open to interpretation in clinical practice.

| Table 1: DSM-5 ARFID Diagnostic Criteria A and ARFID Subtypes | |

| Criteria A | An eating or feeding disturbance as manifested by persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs associated with one (or more) of the following: |

| A1 | Significant weight loss |

| A2 | Significant nutritional deficiency |

| A3 | Dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements |

| A4 | Marked interference with psychosocial functioning |

| Three ARFID Subtypes: | |

| 1 | Apparent lack of interest in eating or food |

| 2 | Avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food |

| 3 | Concern about aversive consequences of eating |

Investigations

How to assess ARFIDs in DGBI?

Although there are a range of available assessment methods and tools none are validated in a DGBI population and all have their individual issues (table 2). Practically to recognise an ARFID presentation clinicians can use the DSM-5 or ICD-11 criteria, however a sound knowledge of ARFIDs plus other eating and mental disorders would be desirable. To assist clinicians in their assessment and understanding of ARFID the Maudsley provide a training course on the PARDI6 (table 2). In the authors opinion this is the most useful course for clinicians working in gastroenterology. The course will help clinicians recognise and assess the severity of an ARFID presentation.

Although the above strategy can assist the recognition of ARFID there is a lack of routes to formal diagnosis and treatment. If a patient meets strict definitions of diagnostic criteria they can be referred to the appropriate local eating disorder service for a full assessment. However clinical experiences suggests referrals to ED services for either ARFID diagnostic assessment or treatment are likely to be rejected.

| Table 2: Assessment Methods for Screening and Diagnosing ARFIDs | ||

| Assessment Method | Assessment Tool | Validation in ARFID |

| Diagnostic: Structured / semi-structured clinical interviews | Eating Disorder Assessment for DSM-5 (EDA-5) | Not specifically validated for ARFID |

| Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders – Clinical Version (SCID-5-CV) | Not specifically validated for ARFID | |

| Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview (PARDI) | Yes in children and adults but takes ~1 hour and not practical for routine use in clinical settings | |

| Eating Disorder Examination ARFID module (EDE ARFID) | Initial validation in children but lengthy in time and not practical for routine clinical practice | |

| Screening: Self Screen Question-naires | Nine-Item ARFID Screen (NIAS) | No, but initial validation suggests better use when used with Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) |

| Fear of Food Questionnaire | No, however it may have future use in DGBI with ARFID fear subtype for assessment and treatment | |

| Pica, ARFID and Rumination Disorder Interview ARFID Questionnaire (PARDI-AR-Q) | Initial validation suggests; Yes in adolescents and adults | |

Management/Discussion

What do we know about the prevalence of ARFID in DGBI?

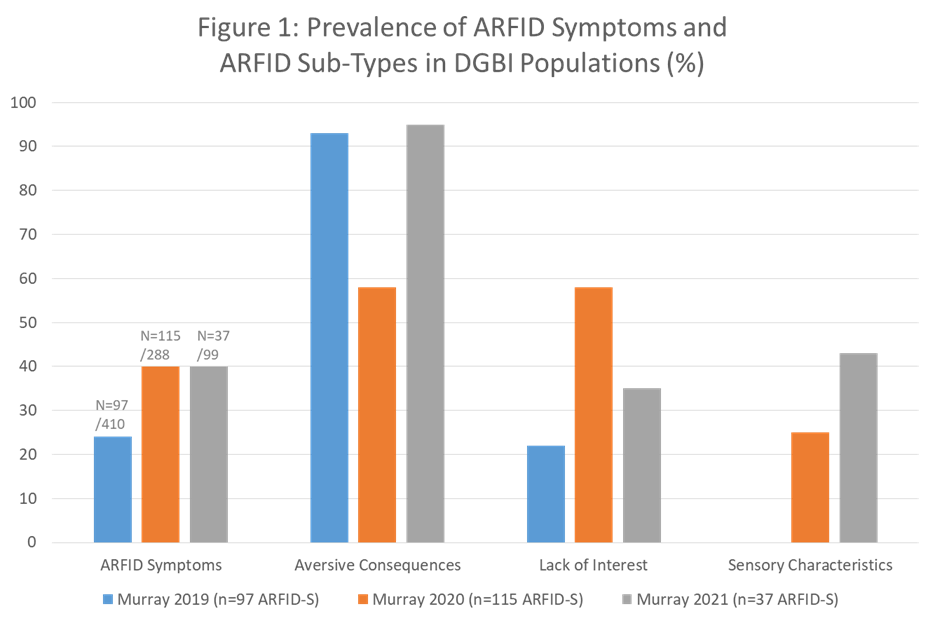

Research in adults with DGBI and ARFID is currently limited to three full publications all from the same author on populations from the USA3,7,8. The literature focuses on ARFID symptoms (ARFID-S) rather than an ARFID Eating Disorder (ARFID-ED), within the DGBI population. Figure one summarises the prevalence rates of ARFID-S (range 24-40%) and the spread of ARFID subtypes for which the fear of aversive consequences is the most common. The data comes from predominantly tertiary neurogastroenterology care and each study used different assessment methods limiting understanding and generalisability.

What do we know about the treatment of ARFID in DGBI?

Currently there is one feasibility study in a DGBI population (n=14) which suggests treatment can be provided within a GI service using 8 sessions of exposure based CBT (all patients were diagnosed with ARFID by a psychologist)9. However in this study over half of participants were also on, or had recently started, a central neuromodulator at the start of the CBT, none were on enteral tube feeding (ETF), only a minority were underweight and is was not clear if any of them were still losing weight when treatment started. Finally no severity levels of ARFID were provided and therefore one can assume lenient definitions were applied and these patients had ARFID-S rather than an ARFID-ED. Additionally although this study suggests a ‘novel’ treatment, this approach has also been used in DGBI previously (prior to ARFID diagnostic criteria) with the exposure element of the CBT leading to improved efficacy in both adults10,11 and adolescents12.

Practically what are the treatment options?

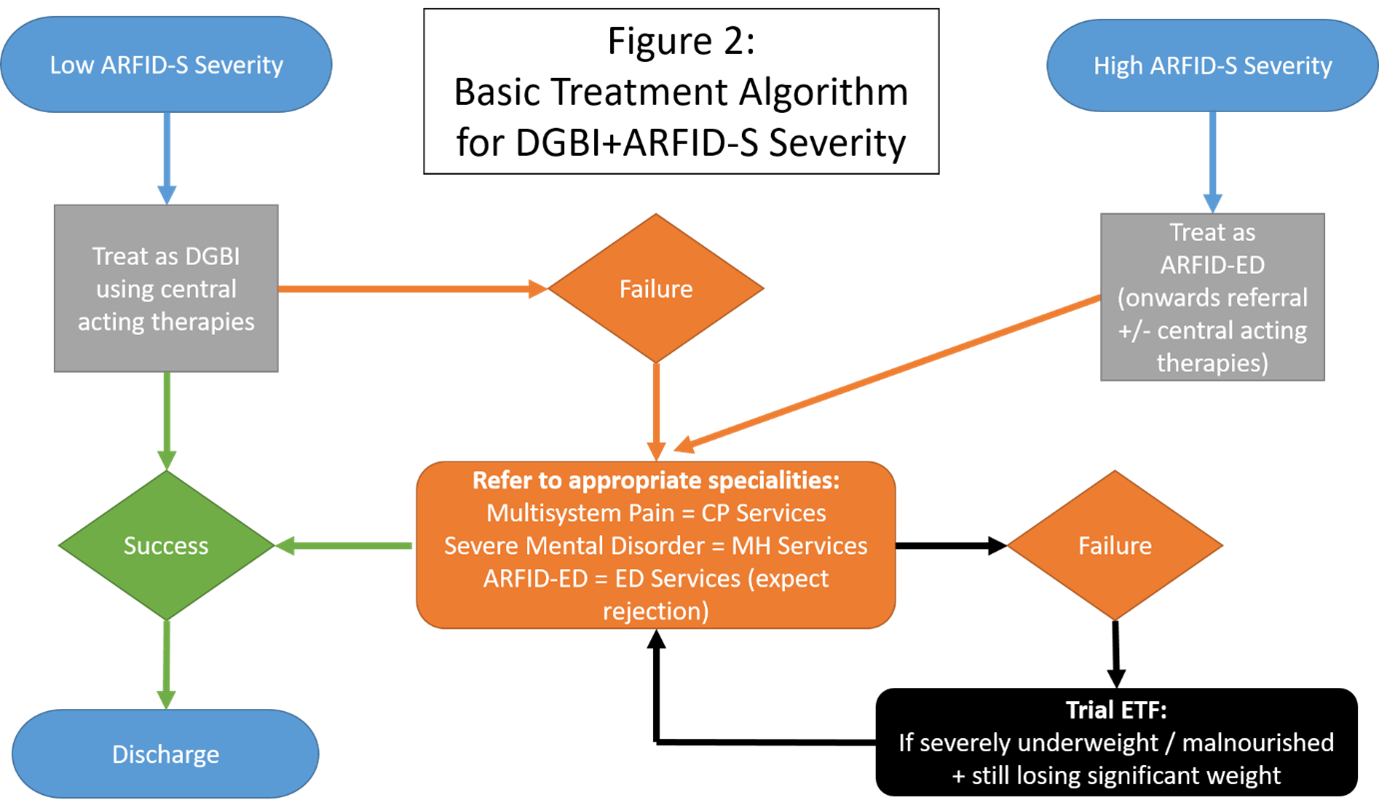

There is currently no defined pathway for managing DGBI+ARFID-S although a practical approach to treatment is provided in figure 2. In patients who present with DGBI+ARFID-S treatments needs to target the maintaining central mechanisms for which anxiety is a key feature. In the authors experience the use of central neuromodulators and/or gut focused behavioural therapies (CBT / Hypnotherapy), combined with an exposure element, can be effective in treating the low ARFID-S severity in DGBI. However for the more severe ARFID presentation, for example where BMI ≤16, then in our tertiary care experience these approaches are rarely effective and more intensive psychological support is required, ideally from an ARFID ED service, or more realistically an appropriate specialist service with psychological expertise e.g. chronic pain (CP) and mental health (MH) services. If this is not available then GI inpatient admission may provide an intensive short term option to implement central acting therapies (neuromodulators and psychology) and education. If ongoing weight loss is present the use of ETF to stabilise severe malnutrition may be required; while attempts are still required to get the patient the correct psychological support (figure 2). In paediatric ARFID there are observed negative effects of ETF, in particular concerning tube dependency (requires the tube for nutrition) and psychological tube dependency (overreliance or perceived need of the tube)13. How many adult patients with DGBI+ARFID-S who are commenced on ETF, then develop psychological tube dependency is unknown. However the risk of creating and fostering tube dependency in an individual must be thought of as part of the MDT management. To quote leading professionals in this field ‘more research is needed to determine when and whether the risks of tube feeding outweigh the benefits in the treatment of low-weight patients with ARFID’14. For those who do present with a very low BMI, similar to what would be observed in anorexia nervosa, the recent Medical Emergencies in Eating Disorders (MEED) guidelines provide a framework for managing the clinical level of risk that severe malnutrition presents with15.

Conclusion

ARFIDs is the most heterogeneous ED in the DSM-516 while DGBIs are also heterogeneous and when the two collide it can be almost impossible to differentiate between ARFID-S or a true ARFID-ED. The current DGBI+ARFID literature does not allow for firm conclusions to be drawn and much like the ARFID diagnosis itself is open to personal clinical interpretation. Currently a quarter to nearly half of DGBI seen in tertiary care experience ARFID-S; for which a biopsychosocial model and intensive outpatient psychological support is required for treatment. In GI services we are in desperate need of access to better psychological support to help manage these patients. For those who present with severe ARFIDs and are more likely to actually have an ARFID-ED then improved referral pathways to ED services and/or combined ED & GI, or indeed combined CP & GI services, are required to manage these patients and may in addition help avoid ETF.

Case: So what do you do…?

Weight Assessment: Only lost 1kg in last 1 months, prior to rapid weight loss, there is therefore time to implement central acting therapies (as above; central neuromodulators / GI psychology, psychology / psychiatry) prior to invasive nutrition support.

Psych Assessment: GAD-7 indicates severe anxiety (≥15), therefore further management options could include medications for anxiety and/or speak to GP for anxiety medication support / IAPT services.

GI Symptom Assessment: Pain is predominant but also across multiple regions therefore referral to local pain team is an option.

GI Service Options:

Central neuromodulators: Choice focused on anxiety and pain e.g. duloxetine

If available refer to GI psychology and Dietitian for behavioural therapy plus graded food exposure; ideally quick and intensive input +/- central neuromodulator

Adult ARFID services for this patient’s presentation do not exist.

Author Biography

Lee Martin, MSc RD Neurogastroenterology Dietitian

Lee works at University College London Hospital (UCLH) as a Neurogastroenterology Dietitian. In this role he works closely with the GI Physiology Unit and Neurogastroenterology Consultants in both inpatient and outpatient settings, seeing adults and adolescents. Lee holds an Honorary Lecture role at University College London and supervises MSc Students.

He has previously worked in academia researching IBS and the FODMAP diet at King’s College London, under the tutelage of Professor Kevin Whelan. He is always keen on research collaborations with a focus on integrating dietetic and psychological and/or psychopharmacological therapies.

Lee is always happy to discuss challenging dietetic cases [email protected]

CME

Clinical updates on the diagnosis and management of functional dyspepsia

02 January 2024

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

03 October 2023

- Disorders 5th Edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. doi:10.1176/APPI.BOOKS.9780890425596

- Claudino AM, Pike KM, Hay P, et al. The classification of feeding and eating disorders in the ICD-11: Results of a field study comparing proposed ICD-11 guidelines with existing ICD-10 guidelines. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):1-17. doi:10.1186/S12916-019-1327-4/TABLES/5

- Murray HB, Bailey AP, Keshishian AC, et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in Adult Neurogastroenterology Patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(9):1995-2002.e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.030

- Harshman SG, Jo J, Kuhnle M, et al. A Moving Target: How We Define Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Can Double Its Prevalence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(5). doi:10.4088/JCP.20M13831

- Eddy KT, Harshman SG, Becker KR, et al. Radcliffe ARFID Workgroup: Toward operationalization of research diagnostic criteria and directions for the field. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(4):361-366. doi:10.1002/EAT.23042

- South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Pica, ARFID, and Rumination Disorder Interview (PARDI) Training. Maudsley Centre for Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders. https://mccaed.slam.nhs.uk/professionals/events/. Published 2023. Accessed March 20, 2023.

- Burton Murray H, Jehangir A, Silvernale CJ, Kuo B, Parkman HP. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder symptoms are frequent in patients presenting for symptoms of gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(12):e13931. doi:10.1111/NMO.13931

- Burton Murray H, Riddle M, Rao F, et al. Eating disorder symptoms, including avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, in patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022;34(8):e14258. doi:10.1111/NMO.14258

- Burton Murray H, Weeks I, Becker KR, et al. Development of a brief cognitive-behavioral treatment for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in the context of disorders of gut–brain interaction: Initial feasibility, acceptability, and clinical outcomes. Int J Eat Disord. 2023;56(3):616-627. doi:10.1002/EAT.23874

- Hesser H, Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Andersson E, Lindfors P, Ljótsson B. How does exposure therapy workγ A comparison between generic and gastrointestinal anxiety-specific mediators in a dismantling study of exposure therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(3):254-267. doi:10.1037/CCP0000273

- Craske MG, Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Labus J, et al. A cognitive-behavioral treatment for irritable bowel syndrome using interoceptive exposure to visceral sensations. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(6-7):413-421. doi:10.1016/J.BRAT.2011.04.001

- Bonnert M, Olén O, Bjureberg J, et al. The role of avoidance behavior in the treatment of adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: A mediation analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2018;105:27-35. doi:10.1016/J.BRAT.2018.03.006

- Dovey TM, Wilken M, Martin CI, Meyer C. Definitions and Clinical Guidance on the Enteral Dependence Component of the Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Diagnostic Criteria in Children. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2018;42(3):499-507. doi:10.1177/0148607117718479

- Thomas JJ, Lawson EA, Micali N, Misra M, Deckersbach T, Eddy KT. Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: A Three-Dimensional Model of Neurobiology with Implications for Etiology and Treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(8):54. doi:10.1007/S11920-017-0795-5

- RCPSYCH. Medical emergencies in eating disorders (MEED): Guidance on recognition and management (CR233). The Royal College of Psychiatrists. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/campaigning-for-better-mental-health-policy/college-reports/2022-college-reports/cr233. Published 2022. Accessed July 28, 2023.

- Sharp WG, Stubbs KH. Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder: A diagnosis at the intersection of feeding and eating disorders necessitating subtype differentiation. Int J Eat Disord. 2019;52(4):398-401. doi:10.1002/EAT.22987