Learning points

- The reader will learn how to apply the evidences of the literature in the management of chronic constipation in clinical practice

- Readers will learn how to define refractory constipation

- Readers will learn how to manage and investigate refractory constipation according to the available evidence in the literature

Introduction

Chronic constipation is one of the most prevalent gastrointestinal conditions presenting to primary care, gastroenterologists, and surgeons globally (estimated pooled prevalence 14%).1 It represents a significant cost for health-care systems worldwide.1 Data collected in the Hospital Episode Statistics database (Copyright NHS Digital, 2018) from the end of 2017 to the end of 2018 in England documented that 71,430 people were admitted to hospital with constipation, equating to 196 people per day.2 NHS England spent £162 million on treating the condition during this period.2 Admissions are likely to be driven by patients not responding to current treatments, although it is also possible that clinicians find it difficult to treat patients with constipation due to lack of guidance on how to investigate appropriately and manage the condition with medication or other more novel therapies. Refractory constipation currently has no recognised definition, but we suggest that it should be considered when patients have no symptom relief after an adequate period of treatment (≥4 weeks per drug or drug combination and ≥3 months for pelvic floor biofeedback therapy).3 This article offers a practical guide to managing refractory constipation, based on current evidence and the experience of the authors.

Diagnosis

Chronic constipation is characterised by several symptoms, including hard stools, excessive straining, infrequent bowel movements, and/or a feeling of incomplete evacuation, as defined by the Rome criteria.4 When these symptoms are associated with abdominal pain that is relieved by, aggravated by, or related to defecation, the diagnosis should be irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C).4 When pain is not a prominent feature, the diagnosed should be functional constipation (FC). These criteria need to be accompanied by exclusion of organic diseases that could have similar presentation, such as coeliac or inflammatory bowel disease and cancer (mainly colorectal or gynaecological).4 A prospective cross-sectional survey and several cohort studies have demonstrated no increase in prevalence of colonic cancer in patients or individuals with constipation compared to general population.5 In women, however, clinicians should be always vigilant of the possibility of ovarian cancer.4 Secondary causes of constipation, such as drugs and neurological diseases, should also be excluded.4

Management

Pharmacological and behavioural treatment

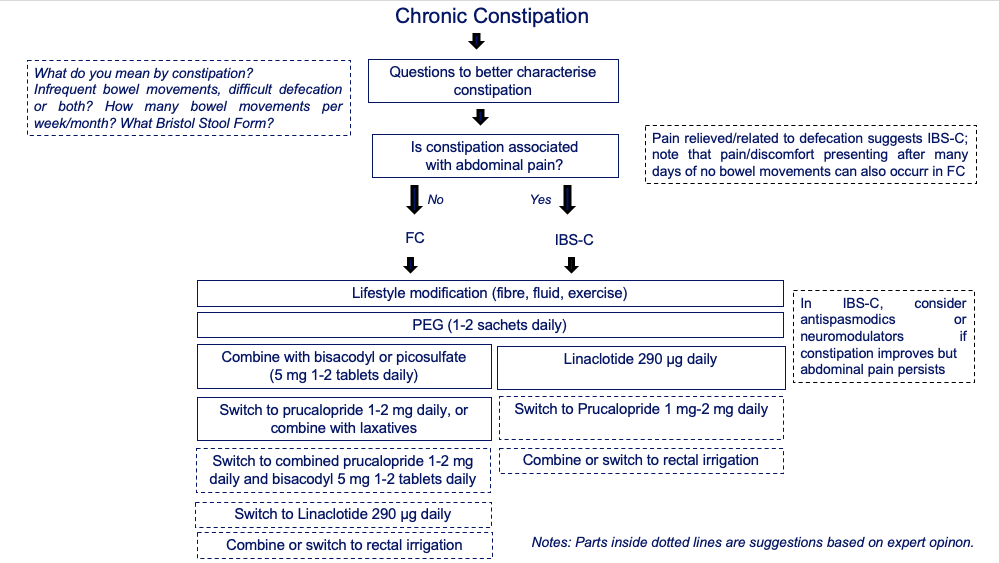

Most patients with FC and IBS-C self-manage their constipation by lifestyle and dietary adjustments and over-the-counter laxatives.3 For those who seek medical attention, the algorithm shown in Figure 1 provides guidance on the use of drugs that have been proved be more effective than placebo and are licensed in the UK for FC and IBS-C. In patients who do not respond to current treatment strategies, anorectal manometry with a balloon expulsion test should be requested. This test enables identification of dys-synergic defecation that can be treated with pelvic floor biofeedback therapies.3 Inability to expel the balloon over specified amounts of time predicts that patients are more likely to respond to biofeedback therapy.6 In centres where this test and biofeedback therapy are both readily available, they could be considered earlier in the treatment process. Evaluation of colonic transit and/or defecography are not recommended before pharmacological treatments are started, as they do not predict response to treatment.7

Although there are no internationally recognised definitions of refractory constipation (in either FC or IBS-C), we recommend basing this diagnosis on inadequate improvement in constipation symptoms (ideally evaluated on an objective scale), despite adequate pharmacological and/or behavioural therapy.3 It is important to remember that in patients with IBS-C, the response to treatment might involve an improvement in constipation symptoms but not abdominal pain, or vice versa. In patients who continue to experience pain symptoms, combination therapy including medications that act on pain, such as neuromodulators (for example tricyclic antidepressants or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), should be considered (Figure 1).

Further investigations

When a patient is refractory to pharmacological and behavioural treatments, the next step is to evaluate whether an alteration in gut motility and/or the presence of anatomical abnormality could be contributing to symptoms.3 Different techniques are available to study colonic transit (radiopaque markers, scintigraphy, and wireless capsule), but those evaluating the whole gut transit are more useful to exclude disorders involving both the upper (gastroparesis) and lower (delayed colonic transit) gastrointestinal tracts.6 Defecography is useful to evaluate the concurrent presence of anorectal anatomical abnormalities.6 Patients with isolated slow colonic transit constipation and no defecation disorder who are non-responsive to treatment can be referred to a multi-disciplinary team to discuss possible surgical options, including anterograde colonic enemas through an appendiceal conduit, ileostomy or total colectomy.3 Before surgery, colonic manometry should be performed, if available, to identify colonic inertia, which is defined by impaired responses to a meal and pharmacological stimulation with bisacodyl or neostigmine.3

Patients with slow transit refractory constipation associated with alteration of upper gastrointestinal motility, such as gastroparesis, are not generally candidates for surgical options. Surgery could be considered as a last resort, although the evidence of benefit is weak and is almost exclusively derived from observational studies.8 A systematic review indicated that colectomy might benefit some patients with refractory slow transit constipation, but was associated with high risk of both short-term and long-term morbidity.9 Of note, abdominal pain is a negative predictor of surgical success.9 Surgery should be avoided in patients who have an isolated anatomical abnormality, such as a rectocele. It remains unclear whether these anatomical abnormalities play a role in constipation symptoms and whether surgical correction can provide a safe and long-term treatment of symptoms.10

Trans-anal irrigation, also known as rectal irrigation, is useful for managing some patients with constipation, but the evidence base remains small with mostly retrospective reports, and this treatment should be performed only after appropriate training.3

Conclusions

Until an internationally recognised definition of refractory constipation becomes accepted, we suggest application of this term to patients with a diagnosis of FC or IBS-C who have not responded to adequate trials of pharmacological and behavioural treatments. In these patients, further evaluation, such as gut transit and motility studies, can help with the identification of the small percentage who could benefit from management in a tertiary level specialist motility centre or even from surgery.

Figure 1. Algorithm summarising the pharmacological and non-pharmacological options to consider in the management of patients with chronic constipation Patients are separated into subgroups of those without prevalent pain or FC and those with pain relieved by, aggravated by, or related to defecation and constipation IBS-C, based on available evidence in the literature and authors’ experience (boxes with dashed outlines). Abbreviations: IBS-C, irritable bowel syndrome with constipation; FC, functional constipation; PEG, polyethylene glycol solution.

Author Biographies

Maura Corsetti

Maura Corsetti is Associate Professor in Gastroenterology at the Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre where she leads the GI Motility Service and she is the referral consultant for functional disorders of upper and lower GI tract. She obtained her Specialization (2000) and PhD (2004) in Italy, where she worked for eight years as referral consultant for functional bowel disorders and lead of the Motility Unit of one of the most important university hospitals in Milan, the San Raffaele University Hospital. She then moved to Belgium, where she spent also part of her PhD, to work in the lab of Prof Jan Tack as Senior Research Supervisor (2012-2016). She is internationally recognized as an expert in this field, as testified by the appointment as Clinical Editor of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, the official journal of the European and American Society of the Neurogastroenterology and Motility.

Victoria Wilkinson-Smith

Victoria Wilkinson-Smith is a current NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow in Gastroenterology, working as an ST1 at the Royal Derby Hospital. Having completed her medical and foundation training in the East Midlands, she has recently come to the end of a 3 year PhD programme at the Nottingham Digestive Diseases Centre where she worked with Prof Spiller and Dr Corsetti looking at GI motility and the use of MRI and other novel techniques in its assessment.

CME

Management of Bloating

29 May 2025

Masterclass: Narcotic Bowel Syndrome

10 February 2025

Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction

28 October 2024

- Suares NC, Ford AC. Prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic idiopathic constipation in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis. A J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1582-1591.

- Disney B. Bowel Interest Group, cost of constipation report. Second edition 2019. https://www.coloplast.co.uk/Global/UK/Continence/Cost%20of%20Constipation%202019.pdf (accessed May 21, 2020).

- Wilkinson-Smith V, Bharucha AE, Emmanuel A, Knowles C, Yiannakou Y, Corsetti M. When all seems lost: management of refractory constipation—surgery, rectal irrigation, percutaneous endoscopic colostomy, and more. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;30:e13352.

- Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1393-1407.e5.

- Power AM, Talley NJ, Ford AC. Association between constipation and colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:894-903.

- Bharucha A, Pemberton JH, Locke GR 3rd. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology 2013;144:218-238.

- Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Stanghellini V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic constipation—a European perspective. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011;23:697-710.

- Aziz I, Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, Simrén M. An approach to the diagnosis and management of Rome IV functional disorders of chronic constipation. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;14:39-46.

- Knowles CH, Grossi U, Chapman M, Mason J; NIHR CapaCiTY working group; Pelvic floor Society. Surgery for constipation: systematic review and practice recommendations. Results I: colonic resection. Colorectal Dis 2017;19(suppl 3):17-36.

- Basilisco G, Corsetti M. Letter: limitations of defecography among patients with refractory constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;50:111-112.