The new exciting content of BSG web education is live. Challenge your diagnostic skills and learn from the experts in the field! Endoscopy case series and Bite Size take you through a patient’s case and offer concise and up-to-date knowledge on less common conditions. #takethechallange #takeabite

A 75-year-old gentleman with a medical history of glaucoma and hypertension was presented to the acute medical admissions unit with insidious weight loss over 18 months and more rapid weight loss of 4kg in the preceding 2 weeks. He had also been complaining of anorexia, lower back pain, general malaise, and increased urinary frequency and urgency. He underwent investigation with blood tests, upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, and cross-sectional imaging.

The blood results were as follows:

| Hb | 80 g/L | (130‒180) |

| WCC | 3.6 x 109/L | (4‒10) |

| MCV | 85.4 fL | (77‒101) |

| Plat | 94 x 109/L | (150‒450) |

| Na | 148 mmol/L | (133‒146) |

| K | 4.1 mmol/L | (3.5‒4.3) |

| Urea | 18.0 mmol/L | (2.8‒7.2) |

| Creat | 201 µmol/L | (59‒104) |

| Glucose | 3.0 mmol/L | (4.0‒5.4) |

| Bili | 15 U/L | (0‒21) |

| ALP | 156 U/L | (30‒120) |

| ALT | 39 U/L | (0‒40) |

| AST | 22 U/L | (0‒40) |

| Alb | 33 g/L | (35‒50) |

| Tot-Ca | 3.1 mmol/L | (2.2‒2.6) |

| Adj-Ca | 3.34 mmol/L | (2.2‒2.6) |

| Phosph | 0.79 mmol/L | (0.8‒1.5) |

| CRP | 69.4 mg/L | (0‒5) |

| SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR | Negative |

During the endoscopy, lesions were found on the gastric greater curve, as well as in the second part of the duodenum (Figures 1 and 2). A CT was subsequently organised (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Lesion on the lower gastric greater curve

Figure 2: Lesions in the second part of the duodenum

Figure 3: Coronal slice from CT of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis

Author Biographies

Dr John Jacob is a Consultant Gastroenterologist and Therapeutic Endoscopist at University Hospital North Tees & Hartlepool NHS Foundation Trust.

Dr Bjorn Rembacken is a Consultant Gastroenterologist and Specialist Endoscopist at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

Dr Chris Bacon is a Senior Lecturer in Haematopathology at Newcastle University and an Honorary Consultant Haematopathologist at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Q&A

-

Answer is e.

The gastric lesion showed the typical appearance of GI lymphoma with engorged red mucosal folds and ulceration, and the duodenal lesion was well demarcated, depressed, fissured, and contained blunted white tipped villi. The CT scan demonstrated marked splenomegaly, retroperitoneal, axillary and cervical lymphadenopathy. The GI tract is the commonest site of extra-nodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounting for 30‒40% of cases.1 Of these, 60‒70% are found in the stomach and 20‒35% in the small bowel; only 5‒10% occur in the colorectum.2 GI lymphomas are more common in males and typically present in the sixth decade of life. They can manifest with a multitude of symptoms, such as dyspepsia, nausea, pain, bloating, diarrhoea, bleeding, obstruction, and weight loss.3

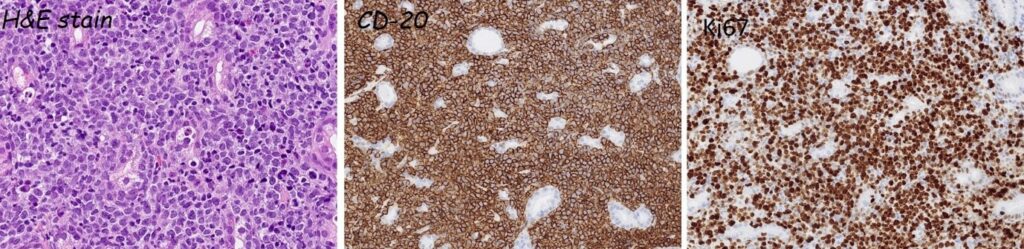

Figure 4: Gastric biopsy stained with H&E, CD-20, and Ki67 stains

-

Answer is d.

Gastric and intestinal biopsy samples contained a diffuse infiltrate of large atypical lymphoid cells expressing the B-cell antigens CD20 and CD79a. They expressed BCL6 but not CD10 or IRF4, indicating a germinal centre B-cell immunophenotype (Hans classifier). In situ hybridisation for Epstein‒Barr virus was negative. Approximately 90% of the atypical B cells expressed the cell-cycle protein Ki67. Interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation showed no evidence of MYC gene rearrangement. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma not otherwise specified was diagnosed. There was no evidence of a low-grade lymphoma component and no Helicobacter spp were identified.

-

Answer is c.

According to the European Society of Medical Oncology4 and British Committee for Standards in Haematology guidelines,5 PET-CT showing focal or diffuse uptake in bone marrow is more sensitive and specific than biopsy to detect bone-marrow infiltration. For this reason, bone-marrow biopsy is now mainly reserved for cases in which a PET-CT is negative but in which a positive biopsy would change management. Left-ventricular function should be assessed by echocardiography before deciding on management because chemotherapy is potentially cardiotoxic in patients above the age of 65 years. Neuraxial MRI is reserved for suspected CNS involvement.

-

Answer is b.

Generally, patients with advanced-stage disease are treated with six to eight cycles of R-CHOP-21 (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone Rx combined with six doses of rituximab) every 21 days. Involved-field radiotherapy is sometimes used as an adjunct in young patients with bulky disease and low to intermediate risk.

Central nervous system prophylaxis is a controversial area, but high dose intravenous methotrexate is increasingly being used for high risk patients.6 Poor prognostic factors include age above 60 years, stage III/IV Ann Arbor classification, poor performance status (patients generally unable to carry out the activities of normal life, such as shopping), more than one extra-nodal site, higher age-adjusted score on the International Prognostic Index, and greater maximum bulk of disease.

Response to treatment is generally monitored with PET-CT scans and careful clinical evaluation every 3 months for 1 year, every 6 months for the following 2 years, and once per year thereafter.4 Our patient, who presented with stage IV disease, has so far had an excellent response to treatment with no nodal disease and marked reduction of splenomegaly on CT (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Post-treatment CT showing excellent response with disappearance of the abnormally enlarged lymph nodes seen before treatment

- Thomas A, Schwartz M, Quigley E. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: the new mimic. BMJ Open Gastro 2019;6:e000320.

- Barakat M. Endoscopic features of primary small bowel lymphoma: a proposed endoscopic classification. Gut 1982;23:36-41.

- Vetro C, Romano A, Amico I, et.al. Endoscopic features of gastrointestinal lymphomas: From diagnosis to follow up. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:12993-13005.

- Tilly H, Vitolo U, Walewski J, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow up. Annals of Oncology 26 (Supplement 5): v116-v125, 2015.

- Chaganti S, Illidge T, Barrington S, et al. Guidelines for the management of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2016;174:43-56.

- McKay P, Wilson MR, Chaganti S, et al. The prevention of central nervous system relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a British Society for Haematology good practice paper. Br J Haematol 2020:190;708-714.