Introduction

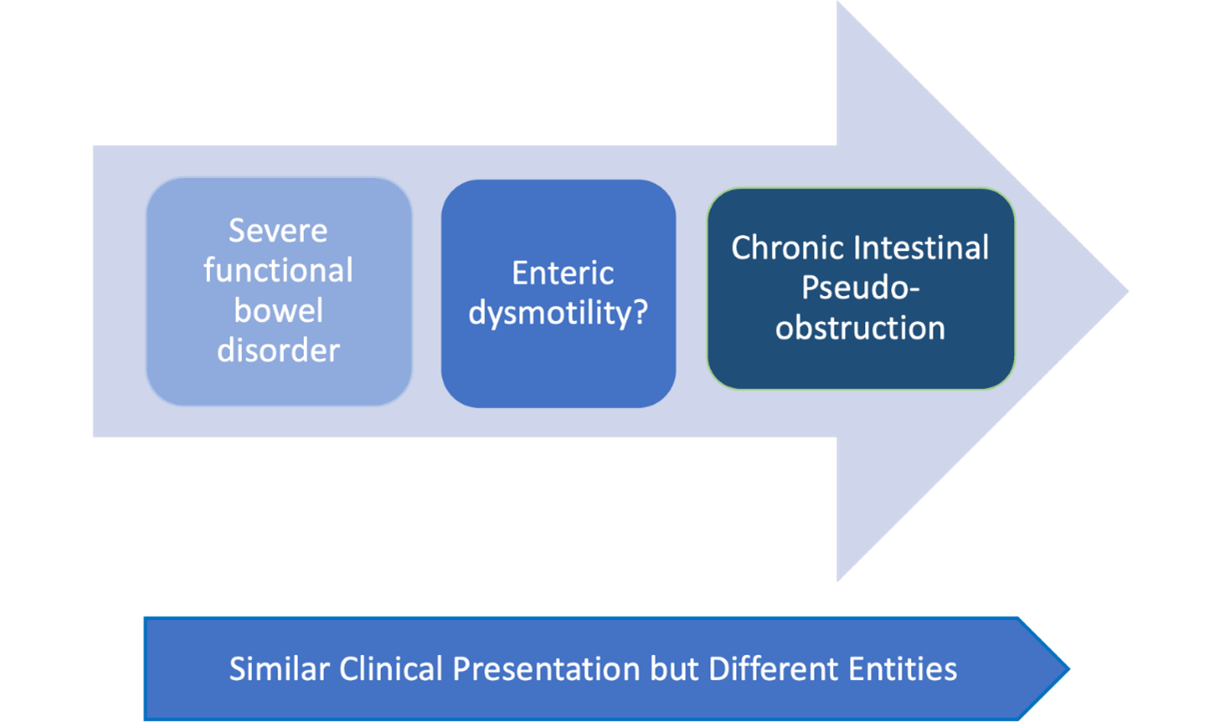

Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) is a highly debilitating motility disorder of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). It is characterised by non-specific signs and symptoms suggestive of intestinal obstruction in the absence of any mechanical obstruction, with radiological features of dilated small or large intestine (Figure 1). CIPO can be challenging to diagnose as it often mimicks the clinical presentations of other gastrointestinal sensorimotor disorders, including enteric dysmotility or functional GI disorders (Figure 2). Delays in diagnosis can result in long-term complications, including malnutrition.1,2 Although CIPO presents more frequently congenitally within the paediatric population, this article solely focuses on the approaches of CIPO in adults.

Figure 1. Small and large bowel dilatation characteristic of CIPO

Epidemiology

CIPO is rare, with limited global data on its prevalence and incidence, likely owing to its poorly defined diagnostic criteria and delayed recognition until advanced stages.1 A nationwide epidemiologic survey in Japan estimated that the population prevalence of CIPO was 9 per million in all ages, with an annual incidence of 2.3 per million people. There was a reported bimodal age distribution with peak frequencies between ages 40 to 49 and 70 to 79, and there was no gender predisposition.1.

Aetiology

Unfortunately, CIPO frequently debuts as an end-stage syndrome manifesting as an intestinal pump insufficiency. The aetiology can be classified into primary and secondary causes. While primary CIPO, by definition, is idiopathic, it can be further sub-classified into three major groups based on histopathology: myopathies, neuropathies, and mesenchymopathies.1 The abnormalities of the smooth muscle cells, intrinsic intestinal and/or extrinsic autonomic nervous system, and interstitial cells of Cajal, respectively, can cause varying degrees of dysmotility through weak bowel contractility or impaired peristalsis.1 Neuropathies are considered the commonest cause of CIPO and can be further categorised as either inflammatory or degenerative on histology.

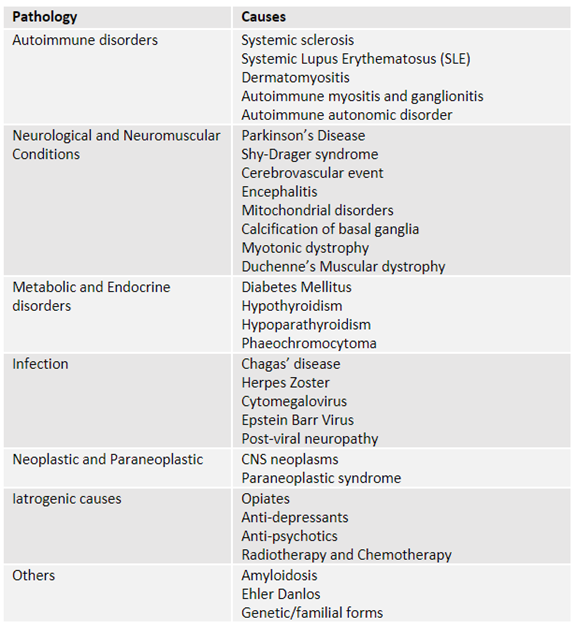

There are numerous causes of secondary CIPO, most of which arise from underlying systemic conditions (table 1).1,5,6

Table 1. Secondary causes of CIPO

Clinical Presentations

The clinical manifestations of CIPO varies depending on the regions of the GIT affected and its underlying cause. Small bowel is frequently worst affected and may present with symptoms such as chronic nausea, vomiting, early satiety, abdominal pain and visible distension, while large bowel involvement may present mainly with abdominal pain, distension and abnormal bowel habit. Some patients with CIPO may present acutely with sudden intense abdominal pain, vomiting and marked abdominal distension, mimicking an acute mechanical intestinal obstruction while other patients endure progressively worsening symptoms, with asymptomatic intervals between short lasting symptomatic episodes for months to years, prior to diagnosis.1,2 In longstanding cases, patients may present with signs of malnutrition and electrolyte disturbances. Abdominal pain during acute episodes of pseudo-obstruction is a typical feature leading to frequent unnecessary and futile diagnostic surgeries and commencing unhelpful, contraindicated opioid therapy.

Diagnostic Approach

A combination of clinical evaluation, radiological imaging, motility studies, serological investigations, and histological examination may be used to diagnose CIPO, its aetiology and aid clinical management.1,2

Clinical history

Patients should be specifically asked about their past medical and surgical history, current medication usage and to explore for undiagnosed neurological, endocrine or connective tissue disorders as listed in Table 1.

Figure 2: CIPO is characterised by radiological distension and intermittent episodes of obstruction whilst enteric dysmotility is a more controversial condition and diagnosis can be established on appropriate motility/transit test in the absence of dilated intestine.

Radiological imaging

Radiological studies, such as abdominal x-rays, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are key to identify bowel loops dilatation. CIPO can only be diagnosed if there is no evidence of a mechanical obstruction.1,2 On the other hand, similar symptoms presentation, including abdominal distension, in the absence of intestinal dilation might be secondary to enteric dysmotility or a functional gastrointestinal disorder (Figure 1 and 2) and both, prognosis and management are distinctively different.

New imaging modalities, such as cine MRI small bowel are promising tools for the diagnosis of this condition (Figure 1).

Laboratory

Blood tests are performed to investigate the aetiology of CIPO and to assess nutritional status. Specialised tests, with a diagnostic purpose, include fasting cortisol, thyroid function tests, anti–CENP and anti-RO antibodies for systemic sclerosis and antineuronal nuclear and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antibodies to rule out paraneoplastic syndromes and autoimmune autonomic disorders, respectively.1,4

Endoscopy

The role of oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and colonoscopy is limited. A venting gastrostomy may be inserted for therapeutic decompression in some patients but requires careful electrolyte monitoring, thus should only be considered only after expert multidisciplinary team discussion.

Manometry

Manometry studies measure the amplitude and spatio-temporal organisation of motility patterns along the GIT to provide information about the integrity and functionality of the enteric neuromuscular apparatus. Small bowel manometry studies allow the differentiation of CIPO from mechanical obstruction and neural from muscular forms of CIPO, although the correlation with histological findings is though poor.1 Small bowel manometry has the theoretical potential to diagnose the disease in the early stages but it is a complex to interpret and perform and is not widely available, thus rarely use in the clinical setting.

Histology

Guidelines have been established to ensure the safe procurement of tissue, outlining histologic techniques, reporting standards and recommendations for referral4. The method for tissue collection and the value of tissue sampling in the diagnosis and management remains a subject of debate. The contention is that laparotomy is the preferred approach when there is still suspicion of mechanical obstruction, allowing for subsequent retrieval of a full-thickness biopsy.4 Risks and benefits need to be carefully considered as there is the added risk of post-operative complications, like prolonged ileus, and findings rarely impact clinical management.

Therapeutic Approaches

There currently is no cure for CIPO. The goals of treatment are to alleviate symptoms, improve nutrition, prevent complications and improve quality of life2,3,5,6,7. BSG guidelines on The Management of adult patients with severe chronic small intestinal dysmotility provide extensive recommendations. More specifically, this includes assessing and establishing safe nutrition for the patient, introduce and avoid medications that improve and negatively affect gut motility, respectively. The management of CIPO requires a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, dieticians, pain team specialists and surgeons with expertise in gut dysmotility.

Prokinetic agents are recommended pharmacological options to enhance intestinal motility. Metoclopramide, domperidone and erythromycin act primarily on upper GIT while prucalopride increases motility throughout the GIT. The efficacy of erythromycin and prucalopride may decrease with long-term use, due to tachyphylaxis. Metoclopramide may precipitate extrapyramidal side effects and long term treatment can cause tardive dyskinesia. Both metoclopramide and domperidone can lead to hyperprolactinemia as well as QTc prolongation on ECG. Pyridostigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, has been reported to improve outcomes but further high-quality studies are required.

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is a known complication of CIPO and can often lead to worsening bloating and diarrhoea and increase the frequency of pseudo-obstruction attacks. There is no international consensus regarding regimens and frequency of antibiotic treatment. According to the American Journal of Gastroenterology, rifaximin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline, metronidazole and neomycin are some of the suggested antibiotics for the treatment of SIBO. These antibiotics can be used when required or in repeated courses, rotating before repeating. It is worth mentioning that metronidazole can cause neuropathy and fluoroquinolones use is now limited in the UK. Following MHRA recommendations. 8

It is key to avoid medications that can impair gut motility, for example, opioids and anti-cholinergics, frequently prescribed to address pain.

In spite of an adequate length of intestine, nutritional support, including enteral feeding or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is fundamental to prevent malnutrition and weight loss. Due to its recurring and progressive nature, CIPO accounts for a proportion of adult patients with chronic intestinal failure, requiring parenteral nutrition.5,6 Careful monitoring of fluid balance to prevent dehydration and electrolyte levels is required, particularly in patients with proximal gastrointestinal stomas. Such ileostomy or venting gastrostomies may be necessary to relieve obstruction. However, these interventions should be considered as a last resort and the risks and benefits be carefully weighed.

Conclusion

CIPO is a rare but debilitating condition that requires a high index of suspicion for early recognition. The diagnosis is usually based on a combination of clinical and radiological investigations. A multidisciplinary approach is critical and treatment options should be individualised and aimed at controlling symptoms, preventing complications and improving the patient’s quality of life.

Author Biographies

Dr Ashley Chut

Medical Doctor, University College London Hospital.

Dr Natalia Zarate-Lopez

Dr Zarate-Lopez graduated and completed her Gastroenterology CCT in Spain where she started her training in the field of Neurogastroenterology under the supervision of founder of the field Prof Malagelada. She then moved to Canada after been awarded a post CCT fellowship by the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology at MacMaster University to develop her PhD. Continued her training as Neurogastroenterologists at the Royal London hospital and UCLH. She is currently one of the GI physiology Unit leads at UCLH, Consultant in Neurogastroenterology, Honorary Consultant at GOSH, lead of the UCLH Adolescent Neurogastro transition service and UCL Associate Professor.

She is passionate about promoting training in the field to guarantee evidenced based experience and management and the development of new technologies to assess gut sensorimotor function. Dr Zarate-Lopez has lectured and published extensively in the field, contributing to the recent European Guidelines in both Functional Dyspepsia and Gastroparesis.

CME

Management of Bloating

29 May 2025

Masterclass: Narcotic Bowel Syndrome

10 February 2025

- Downes TJ, Cheruvu MS, Karunaratne TB, De Giorgio R, Farmer AD. Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(6):477-489. doi:10.1097/MCG.0000000000001047

- Zenzeri L, Tambucci R, Quitadamo P, Giorgio V, De Giorgio R, Di Nardo G. Update on chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2020;36(3):230-237. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000630

- Lida H, Ohkubo H, Inamori M, Nakajima A, Sato H. Epidemiology and clinical experience of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in Japan: a nationwide epidemiologic survey. J Epidemiol. 2013;23(4):288-294. doi:10.2188/jea.je20120173

- Knowles CH, De Giorgio R, Kapur RP, et al. The London Classification of gastrointestinal neuromuscular pathology: report on behalf of the Gastro 2009 International Working Group. Gut. 2010;59(7):882-887. doi:10.1136/gut.2009.200444

- Nightingale JMD, Paine P, McLaughlin J, et al. The management of adult patients with severe chronic small intestinal dysmotility. Gut. 2020;69(12):2074-2092. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321631

- Vasant DH, Pironi L, Barbara G, et al. An international survey on clinicians' perspectives on the diagnosis and management of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and enteric dysmotility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;32(12): e13937. doi:10.1111/nmo.13937

- Nightingale, Paine, McLaughlin, et al. The management of adult patients with severe

chronic small intestinal dysmotility. Gut 2020;0:1:19.

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics: must now only be prescribed when other commonly recommended antibiotics are inappropriate. 22 Jan 2024.