Authors

Dr Frank Phillips, Consultant Gastroenterologist, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust.

Shellie Radford, IBD Nurse Specialist & PhD student, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust & The University of Nottingham.

Dr Gordon Moran, Clinical Associate Professor Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Nottingham

Biological drugs have an important role in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In the majority of patients, they are both effective and safe. However, in some cases they can be associated with significant morbidity and mortality. In the following two case presentations, we focus on two common complications of biologics, more specifically in this case anti-TNF alpha medications.

Adverse cutaneous reactions

This 24-year-old gentleman was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (upper GI and colonic location; inflammatory behaviour; non-smoker) 8 years previously. A year after diagnosis, he started Infliximab 8 weekly 5 mg/kg, after azathioprine resulted in pancreatitis. This kept his luminal disease in symptomatic remission. More recently, methotrexate was added in combination due to low trough Infliximab levels.

Over the last year, he has developed a dry red itchy rash typical of eczema (figure 1). This initially affected his back, then spread to the rest of his torso, then both arms and face. At its worse, his arms have been cracked and bleeding. He has a history of minor childhood eczema.

The addition of methotrexate did not help the eczema, and nor did the use of topical hydrocortisone. After seeing a dermatologist, he was prescribed Fexofenadine 130 mg twice daily, tacrolimus 0.1% ointment for his face and a more potent topical steroid for his body. The infliximab was also stopped and the eczematous rash is now resolving.

Figure 1: extensive eczematous rash involving the torso and upper limbs, due to Infliximab.

Discussion

There are a number of cutaneous complications of anti-TNF treatments in IBD, including injection site and infusion reactions, infectious cutaneous complications and ‘paradoxical’ reactions.1 The latter are dermatoses, so-called because biologics are often used to treat such skin lesions. Paradoxical reactions have an occurrence rate in IBD patients treated with anti-TNF agents of 5-10%,2 and typically occur within 2-6 months of initiation of therapy, although can occur years after initiation.3 There are also rare reports of occurrence with both vedolizumab and ustekinumab use in IBD.4 The most frequent paradoxical reactions are eczematous and psoriasiform reactions, which may be new onset or an exacerbation of existing lesion.5

Interestingly, the occurrence of paradoxical reactions is greater with the use of adalimumab compared to infliximab (4.1% vs 1.3%), and also occurs earlier after anti-TNF initiation (40.7 vs 126.9 weeks).6 Other significant risk factors include female gender and history of psoriasis or eczema, whilst combination therapy with immunomodulator appears to reduce the risk.6

Management of paradoxical reactions depends upon its severity. Most cutaneous lesions can be cleared by simple topical treatments whilst continuing the anti-TNF agent.7 For more severe (extending >5% of body surface or pustulating) or unresponsive lesions, stopping the anti-TNF almost always results in cutaneous lesions clearing. The decision to continue or withdraw the anti-TNF may also be influenced by the degree of control of the underlying IBD. The reintroduction of a second anti-TNF was associated with recurrence or persistence of the cutaneous lesion in approximately 50% of cases, so could be considered if the cutaneous lesion was not severe.8 Another option is to switch to a therapy which may have dual efficacy against the cutaneous lesion and the underlying IBD, such as methotrexate9 or ustekinumab.10

Opportunistic infections

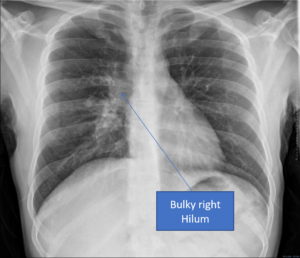

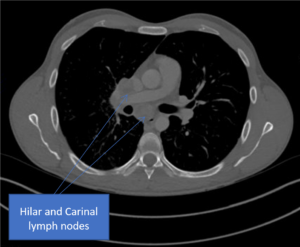

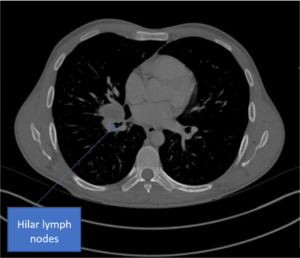

This 33-year-old gentleman was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease (Ileocolonic and perianal location; inflammatory behaviour; non-smoker) 1 year previously. He was started on Infliximab (Remsima) 350mg, 4-weekly, which brought his Crohn’s disease into remission. Prior to infliximab start date, there was a confirmed negative TB PCR.

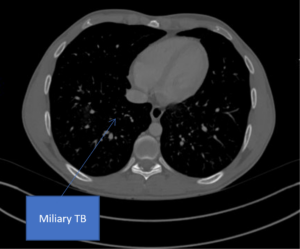

Around 6 months after starting biologic therapy, he presented to accident and emergency with a 1-month history of chest pain, fevers, and coughing. A subsequent diagnosis of latent TB was made following CT scan, biological therapy was stopped, and combination antibiotic treatment was commenced. He was put under the shared care of the respiratory and gastroenterology team. He has since restarted biologic therapy and will undergo careful follow up due to the risk of recurrence of TB.

A

B

C

D

Figure 2. A) Chest radiograph showing a bulky right hilum, B) and C) CT scan showing hilar and carinal lympho nodes, D) CT scan showing military TB.

Discussion

Opportunistic infections (OI) in patients with IBD include viral infections (herpes viruses, human papillomavirus, influenza virus, and JC virus), bacterial infections (tuberculosis, nocardiosis, Clostridium difficile infection, pneumococcal infection, legionellosis, and listeriosis), fungal infections (histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, Pneumocystis jirovecii infection, aspergillosis, and candidiasis), and parasite infections (Strongyloides stercoralis). 11 Although these infections can lead to high morbidity and mortality, only a minority of patients with IBD develop OIs.11 Risk factors for OIs include malnutrition, older age, congenital immunodeficiency, HIV infection, chronic diseases, and use of corticosteroids.11

Anti-TNF therapy doubles the risk of OIs in IBD patients.12 Compared with anti-TNF monotherapy, combination therapy has been associated with increased risks of serious infection (hazard ratio [HR], 1.23; 95% CI, 1.05-1.45) and OI (HR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.32-2.91). Conversely, anti-TNF monotherapy was associated with decreased risk of viral OI compared with thiopurine monotherapy (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.38-0.87). 11,13 Anti-interleukin is associated with a low risk of serious and OIs14, however number of OIs are higher with anti-integrin.15

The use of systemic immunosuppression is not associated with increased risk of contracting COVID-19, as shown in multi-institutional studies in the USA and Europe.16,17 However, the impact of immunosuppression on the severity of COVID-19 disease remains unclear.18 Ongoing research in the UK aims to understand the impact of IBD treatments and physical distancing strategies on COVID-19 through the use of serology testing.19

The BSG recommends that IBD patients commencing immunomodulators or biologics treatment should undergo screening for HBV, HCV and HIV (and VZV if no history of chicken pox, shingles or varicella vaccination) and active or latent TB.20,21 It is unclear whether screening for EBV status should be done routinely in adults.22 ECCO recommends testing for CMV should be reserved for steroid-resistant disease.23 Vaccination program for patients with IBD should be initiated at diagnosis and/or before immunosuppressant therapy.24

Author Biographies

Dr Frank Phillips

Dr Phillips is a Consultant in Gastroenterology & Clinical Nutrition; IBD and Intestinal Failure Specialist at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS trust. He has completed advanced research fellowships in Endoscopy and Inflammatory bowel disease, after completing Intestinal failure and Multi-visceral transplant fellowships in St Marks and Cambridge.

Shellie Jean Radford

Shellie Jean Radford is an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) nurse researcher and PhD student working in the NHS at the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre and Nottingham University. She is passionate about improving the lives of people living with IBD and getting nurses and allied health professions more involved in clinical research. She is the BSG Nurses Association Treasurer and IBD research representative.

Dr Gordon Moran

Dr Moran is an academic gastroenterologist with a special interest in the clinical management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. He has completed his gastroenterology training in Birmingham, UK and his PhD studies at the University of Manchester in 2011. He advanced his clinical training in Inflammatory Bowel Disease by undertaking a one year advanced clinical fellowship in Inflammatory Bowel Disease at the University of Calgary, Canada.

He has been appointed as Clinical Associate Professor in Gastroenterology at the University of Nottingham in 2013, and has been Head of Service for IBD at NUH till 2022. He is a member of the IBD section for the BSG, leads IBD research at the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, and is an IBD expert member for the National Institute of Health Research Trent Clinical Research Network. He leads the 2024 IBD guideline development group of the BSG. To date, he has received over £11 million pounds in grant research income, authored nearly 80 peer-reviewed academic chapters, gave a number of national and international lectures, and supervised 10 PhD students and 3 IBD fellows. His research interest is mainly advanced imaging in IBD, early phase mechanistic studies, and phase II-IV IBD trials. Dr Moran has a very large IBD practice, performs GI endoscopic procedures, and treats complex paediatric and adult IBD across the Midlands.

CME

Top to Bottom Podcast - BSG IBD Guideline - De-escalation of Therapy

14 November 2025

Top to Bottom Podcast - BSG IBD Guideline - Methodology

07 November 2025

BSG Webinar: IBD Highlights from BSG LIVE‘25

22 October 2025

- Mocci G, Marzo M, Papa A, Armuzzi A, Guidi L. Dermatological adverse reactions during anti-TNF treatments: focus on inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(10):769-79.

- Moran GW, Lim AW, Bailey JL, et al. Review article: dermatological complications of immunosuppressive and anti‐TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1002–1024.

- Fiorino G, Danese S, Pariente B, Allez M. Paradoxical immune-mediated inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease patients receiving anti-TNF-α agents. Autoimmun. Rev. 2014;13: 15–19.

- Bhayat F, England D, Blake A. Post-marketing Safety Experience with Vedolizumab: Skin Reactions (Psoriasiform and Eczematous), Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:S313

- Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, Hansel K, Stingeni L, Ardizzone S, Genovese G, Marzano AV, Maconi G. Dermatological Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. J Clin Med. 2021 19;10(2):364.

- Weizman AV, Sharma R, Afzal NM, Xu W, Walsh S, Stempak JM, Nguyen GC, Croitoru K, Steinhart AH, Silverberg MS. Stricturing and fistulizing Crohn’s disease is associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-induced psoriasis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:2430–2438.

- Cleynen I, Van Moerkercke W, Billiet T, et al. Characteristics of Skin Lesions Associated With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):10-22.

- Cullen G, Kroshinsky D, Cheifetz AS, Korzenik JR. Psoriasis associated with anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a new series and a review of 120 cases from the literature. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011 Dec;34(11-12):1318-27.

- Guerra I, Pérez‐Jeldres T, Iborra M, et al. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and management of psoriasis induced by Anti‐TNF therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A nationwide cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:894–901.

- Ezzedine K, Visseaux L, Cadiot G, Brixi H, Bernard P, Reguiai Z. Ustekinumab for Skin Reactions Associated with Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Agents in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. J Dermatol 2019;46:322–327.

- Dave, M., Purohit, T., Razonable, R. & Loftus, E. V. Opportunistic infections due to inflammatory bowel disease therapy. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases 20 196–212 (2014).

- Ford, A. C. & Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Opportunistic infections with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Gastroenterol. 108, 1268–1276 (2013).

- Kirchgesner, J. et al. Risk of Serious and Opportunistic Infections Associated With Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. (2018) doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.012.

- Sandborn, W. J. et al. A Randomized Trial of Ustekinumab, a Human Interleukin-12/23 Monoclonal Antibody, in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 135, 1130–1141 (2008).

- Luthra, P., Peyrin-Biroulet, L. & Ford, A. C. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 41, 1227–1236 (2015).

- Maconi, G. et al. Risk of COVID 19 in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases compared to a control population. Liver Dis. (2021) doi:10.1016/j.dld.2020.12.013.

- Burke, K. E. et al. Immunosuppressive Therapy and Risk of COVID-19 Infection in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Bowel Dis. 27, 155–161 (2021).

- BSG IBD section committee. BSG expanded consensus advice for the management of IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic | The British Society of Gastroenterology. https://bsgorguk.kinsta.cloud/covid-19-advice/bsg-advice-for-management-of-inflammatory-bowel-diseases-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/ (2021).

- CLARITY-IBD. COVID-19 in IBD: CLARITY IBD. https://www.clarityibd.org/.

- Lamb, C. A. et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut (2019) doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318484.

- Walsh, A. J. et al. Implementing guidelines on the prevention of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn’s Colitis 7, (2013).

- Barnes, E. L. & Herfarth, H. H. The Usefulness of Serologic Testing for Epstein–Barr Virus Before Initiation of Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology (2017) doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.055.

- Rahier, J. F. et al. Second European evidence-based consensus on the prevention, diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn’s Colitis 8, 443–468 (2014).

- Shah, B. B. & Goenka, M. K. A comprehensive review of vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: An Indian perspective. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology 39 321–330 (2020).