A 40-year-old female presented to the emergency department with a 4-day history of passing dark stool. On arrival she was tachycardic and complained of feeling lightheaded. She had no abdominal pain. Digital rectal examination revealed the presence of dark red blood and initial investigations show a haemoglobin of 68 g/L and blood urea of 11.2 mmol/L. She was otherwise fit and well and took no medication.

Following initial resuscitative measures and blood transfusion, the patient underwent an OGD. Good views were obtained and there was no evidence of any pathology or active or recent bleeding in her upper GI tract. She continued to bleed so a colonoscopy was performed. This showed a normal colon but altered blood in the terminal ileum. No cause was identified.

Questions

72 hours after her initial presentation, the patient had ongoing rectal bleeding. She required a further blood transfusion but remained haemodynamically stable.

Question 1

72 hours after her initial presentation, the patient had ongoing rectal bleeding. She required a further blood transfusion but remained haemodynamically stable.

Question 2

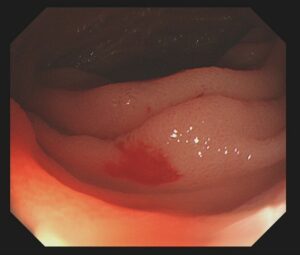

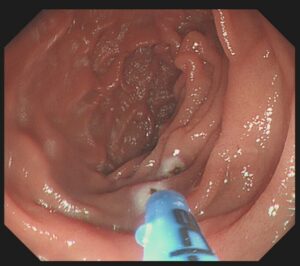

Small-bowel VCE identified a bleeding lesion located in the first small bowel tertile, identified in the images below. Seven days after the patient’s initial presentation, there was clinical evidence of ongoing GI bleeding, requiring regular blood transfusion.

Question 3

Discussion

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is defined as overt or occult bleeding of unknown origin, which persists or recurs after OGD and colonoscopy (Raju et al., 2007). OGIB represents approximately 5% of all gastrointestinal bleeding (Sey & Yan, 2019), the majority of which is caused by bleeding within the small bowel (Fry et al., 2009). Small bowel bleeding may be due to a number of aetiologies, however angioectasia represent the most common single cause, accounting for around 50% of OGIB, followed by inflammatory conditions and ulcers (27%) and neoplasms (9%) (Liao et al., 2010). Angioectasia are more common in older patients and those with co-morbidities such as cardiac and liver disease.

Investigation of OGIB can be challenging. Several direct-visualisation and radiological techniques are available, including video-capsule endoscopy (VCE), double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE) and CT angiography. VCE has been shown to have a superior diagnostic yield to CT angiography in OGIB, particularly for vascular and inflammatory lesions (Saperas et al., 2007). CT angiography is, however, likely to be a more appropriate next investigation following OGD and colonoscopy in the context of large volume haemorrhage or haemodynamic instability.

Meta-analysis of 10 studies which compared VCE to DBE reported a diagnostic yield in VCE of 62% (95% CI 47.3-76.1) which is comparable to DBE (Teshima et al., 2011). Although DBE has a comparable yield to VCE, it is more resource-intense and invasive with a higher risk of complication (Mensink et al., 2007). VCE can also localise the source of bleeding within the small bowel to guide the approach for DBE- antegrade versus retrograde. VCE is therefore recommended as the first-line investigation in OGIB (Pennazio et al., 2015). The European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) recommends that a ‘second-look’ OGD should not routinely be performed in preference to VCE, which should be performed as soon as possible to improve diagnostic yield (Pennazio et al., 2015).

Patients with a negative VCE, without evidence of ongoing bleeding, can be safely managed conservatively and have a low risk of re-bleeding (Lai et al., 2006). For those with positive findings on VCE, device-assisted enteroscopy is recommended (Pennazio et al., 2015). Device-assisted enteroscopy commonly is carried out by either conventional double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) or the newer motorised spiral enteroscopy. DBE has a significantly higher diagnostic yield when used in patients who already have a positive VCE (Teshima et al., 2011) and provides therapeutic possibilities.

Although medical options such as somatostatin analogues and thalidomide are available, if there is no contraindication, device-assisted enteroscopy is recommended in the first instance to provide definitive management (Pennazio et al., 2015).

Author Biographies

Dr Robert Lees

Robert graduated from the University of Edinburgh with BMedSci (Hons) and MBChB in 2016. He is a Gastroenterology Registrar at the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and is currently a clinical research fellowship with a focus on inflammatory bowel disease.

Dr Clare Parker

Clare is a Consultant Gastroenterologist at The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. She is a specialist interested in capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy, is a faculty member of European Capsule Endoscopy Course, and a core contributor to design of the UK training pathway in capsule endoscopy.

Q&A

-

Answer is B.

Angioectasias are the most common single cause of obscure GI bleeding. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 227 studies reported that angioectasia was the identified cause in 50% of cases (Liao et al., 2010).

-

Answer is C.

Small-bowel VCE is recommended as the first line investigation in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (Pennazio et al., 2015). This should be performed as soon as possible after the bleeding episode to maximise diagnostic yield. In acutely unwell patients, who are haemodynamically unstable, a CT angiography would be the most appropriate next investigation after a negative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

-

Answer is A.

This is a young, healthy patient with evidence of active small bowel bleeding and no contraindication to endoscopic management. DBE is therefore the most appropriate next step.

A DBE was performed which identified multiple bleeding angioectasia, likely in the jejunum. These were successfully treated with APC and the patient went on to make a good recovery.

Image 1: Bleeding angioectasia seen at DBE (top) followed by successful APC (bottom)

CME

Newly formed ATSMs in ERCP and BSCP

24 November 2025

National Clinical Endoscopists Conference 2025 Recording

13 November 2025

Quality Indicators in Barrett's Endoscopy: A Quest for the Holy Grail

27 October 2025

- Fry, LC., Bellutti, M., Neumann, H., Malfertheiner, P. and Mönkemüller, K. (2009) ‘Incidence of bleeding lesions within reach of conventional upper and lower endoscopes in patients undergoing double-balloon enteroscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding’, Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 29(3), pp. 342–349.

- Lai, LH., Wong, GL., Chow, DK., Lau, JY., Sung, JJ. and Leung, WK. (2006) ‘Long-term follow-up of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after negative capsule endoscopy’, The American journal of gastroenterology, 101(6), pp. 1224–1228.

- Liao, Z., Gao, R., Xu, C. and Li, ZS. (2010) ‘Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review’, Gastrointest Endosc, 71(2), pp. 280-286.

- Mensink, PB., Haringsma, J., Kucharzik, T., Cellier, C., Pérez-Cuadrado, E., Mönkemüller, K., Gasbarrini, A., Kaffes, AJ., Nakamura, K., Yen, HH. and Yamamoto, H. (2007) ‘Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey’, Endoscopy, 39(7), pp. 613–615.

- Pennazio, M., Spada, C., Eliakim, R., Keuchel, M., May, A., Mulder, C. J., Rondonotti, E., Adler, S. N., Albert, J., Baltes, P., Barbaro, F., Cellier, C., Charton, J. P., Delvaux, M., Despott, E. J., Domagk, D., Klein, A., McAlindon, M., Rosa, B., Rowse, G., Sanders, DS., Saurin, JC., Sidhu, R., Dumonceau, J., Hassan, C and Gralnek, CH., I. M. (2015) ‘Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline’, Endoscopy, 47(4), pp. 352–376.

- Raju GS., Gerson L., Das A. and Lewis B; American Gastroenterological Association. (2007) ‘American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute medical position statement on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding’, Gastroenterology, 133(5), pp. 1694-6.

- Saperas, E., Dot, J., Videla, S., Alvarez-Castells, A., Perez-Lafuente, M., Armengol, JR. and Malagelada, JR. (2007) ‘Capsule endoscopy versus computed tomographic or standard angiography for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding’, The American journal of gastroenterology, 102(4), pp. 731–737.

- Sey, M. and Yan, BM. (2019) ‘Optimal management of the patient presenting with small bowel bleeding. Best practice & research’, Clinical gastroenterology, 42-43, 101611.

- Teshima, CW., Kuipers, EJ., van Zanten, SV. and Mensink, PB. (2011) ‘Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated meta-analysis’, Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 26(5), pp. 796–801.