The new exciting content of BSG web education is live. Challenge your diagnostic skills and learn from the experts in the field! Endoscopy case series and Bite Size take you through a patient’s case and offer concise and up-to-date knowledge on less common conditions. #takethechallange #takeabite

By Sarah Kelly, GI Physiology, Northern General Hospital, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK

Case

A 29-year-old woman was referred for oesophageal physiology testing to assess for evidence of reflux and suitability for anti-reflux surgery. A 2-year history of reflux symptoms, worsening over the last 12 months, was reported in the referral. The patient also reported symptoms of vomiting and belching particularly after eating. Medications included duloxetine and reflux suppressants as required. The symptoms had not responded to treatment with a proton-pump inhibitor. Previous endoscopy had demonstrated a small sliding hiatus hernia but no other abnormalities. A barium swallow test had shown free flow of barium into the stomach, and blood profile and abdominal examination were both normal.

Question 1

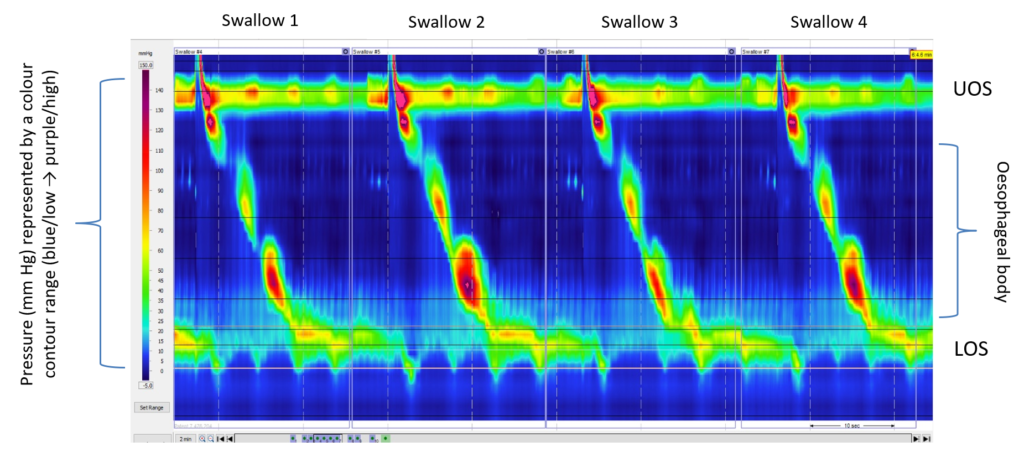

Further questioning found that her main symptom was regurgitation, which was worse after meals and when she was active. The regurgitation occurred without any retching, and she would either swallow the contents or spit it out if appropriate to do so. She also reported frequent belching after meals and only occasional heartburn. High-resolution oesophageal manometry was performed to trace the oesophageal pressure profile during standard test swallows (Figure 1). Data were analysed and categorised based on the Chicago classification.1

Figure 1: High-resolution manometry contour trace during standard test swallows (5 mL water bolus)

Abbreviations: LOS, lower oesophageal sphincter; UOS, upper oesophageal sphincter.

Question 2

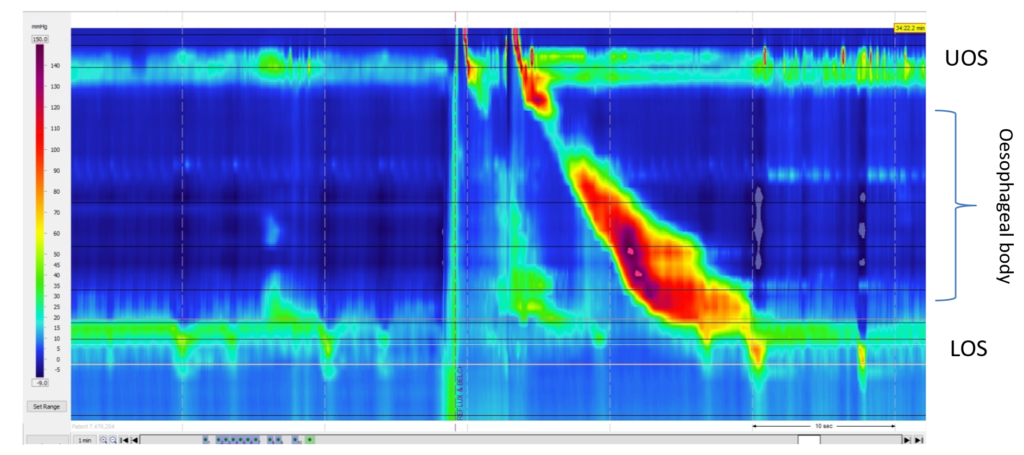

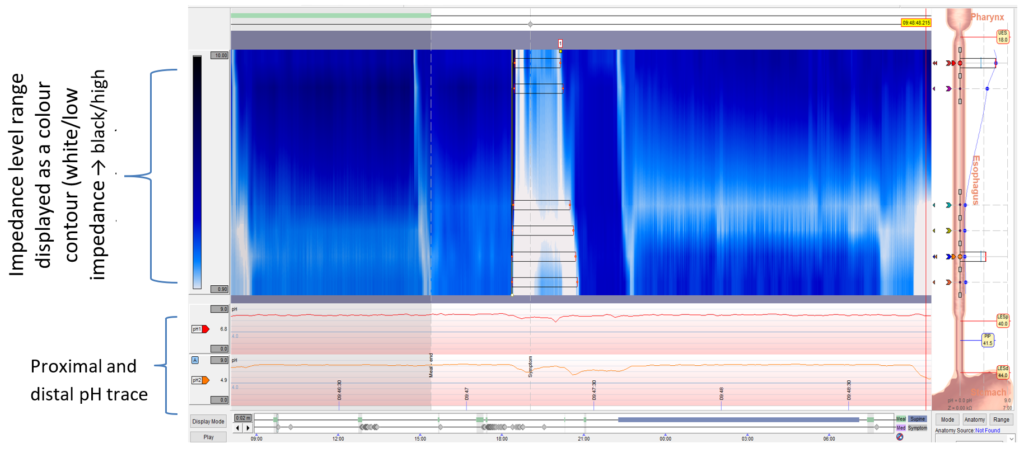

As her main symptom was post-prandial regurgitation, we investigated further by placing an impedance pH catheter alongside the manometry catheter and continued recording during and immediately following a test meal. This test enabled us to monitor bolus movement and oesophageal motility simultaneously (Figure 2).

Figure 2: High-resolution manometry contour trace and recording (A) and corresponding impedance pH trace (B) directly after a test meal

Immediately after eating, the patient documented perceived regurgitation. Abbreviations: LOS, lower oesophageal sphincter; UOS, upper oesophageal sphincter.

Gastric straining was demonstrated on the manometry trace immediately following the test meal, at the same time the patient reported perceived regurgitation. The corresponding impedance trace also demonstrated retrograde non-acidic bolus movement. This behaviour was noted numerous times in the post-prandial recording period.

Question 3

Discussion

Rumination syndrome is an under-recognised disorder. Patients often undergo years of extensive investigations, and various empirical treatments fail to improve symptoms. It is classified as a functional gastroduodenal disorder in the Rome IV Criteria2, and a feeding and eating disorder in the DSM-5.3 Onset is often preceded by a psychological stressor or inciting event, and commonly occurs in the background of depression and or anxiety.4

Rumination is characterised by post-prandial regurgitation caused by voluntary, albeit unconscious, abdominal and diaphragmatic contractions, and is hypothesised to be “a generic abnormal behavioural response to a variety of aversive digestive stimuli”.5 While patients often report their symptoms as episodes of vomiting, the rumination frequently occurs without retching or nausea. As the behaviour typically begins shortly after meal ingestion, initially the regurgitate is not unpleasant and, therefore, can be easily swallowed or spat out until it becomes acidic.6,7

Diagnosis may be made from a comprehensive clinical history. Combined high-resolution oesophageal manometry and impedance testing can support a rumination diagnosis by detecting R waves related to abdominal and diaphragmatic contraction resulting in regurgitation.5 Ambulatory impedance pH monitoring can reveal significant post-prandial non-acidic retrograde bolus movement. Of note, the pH profile changes from non-acidic to acidic over time.8

Studies in the adult and paediatric populations have suggested several rumination subtypes or variants.5,9 Physiological testing can help to clarify the specific mechanism of disease and to direct treatment.

There is no consensus on treatment and reported methods have varied. Murray et al.6 suggest targeted diaphragmatic breathing as a first-line approach. Patients are taught to perform diaphragmatic breathing rather than chest breathing. This technique is associated with relaxation of the muscles responsible for rumination and can also provide a distraction. Patients perform the technique during and after meals to help them suppress the abdominal contractions.

Tucker et al.5 suggest that attending just one behavioural intervention session can produce a lasting clinical benefit in some patients, and among 40 patients reported “complete improvement in rumination and/or belching in 43%” at a median follow-up of 5 months. Partial improvement was seen in 13 (28%) patients. A variety of reports and studies support the suggestion that performing diaphragmatic breathing reduces regurgitation episodes.10‒12 Being able to provide a visual demonstration of the findings can aid patients’ understanding and acceptance of the behavioural element, but also encourage engagement in behavioural therapies.

Where symptoms persist following behavioural intervention, it may be necessary to treat the underlying cause of the digestive symptom that triggers the rumination behaviour. For example, in cases where it is proven that spontaneous reflux events trigger the behavioural response, reflux suppression with medication such as baclofen or surgery may be more effective.

Learning points

- Taking a detailed and thorough history ensures that the patient can describe their symptoms correctly.

- Investigations should follow a standardised test protocol and include adjunctive tests (eg, solid swallows or test meal) as necessary based on the patient’s history.

- Where available, high-resolution impedance manometry is recommended to optimally assess intrabolus pressure, bolus clearance, and bolus flow through the oesophagogastric junction, particularly when behavioural disorders, such as rumination and supragastric belching, are suspected.

- Targeted diaphragmatic breathing is recommended as a first-line approach for treating rumination syndrome.

For a short video demonstrating the diaphragmatic breathing technique, please click here.

Author Biography

Sarah Kelly

Sarah Kelly is the service manager at Sheffield’s IQIPS accredited GI Physiology department, which offers a wide range of upper and lower gastrointestinal physiology investigations and treatments. She is a fully qualified clinical scientist with over 13 years’ experience in clinical gastrointestinal physiology, is involved in research, peer reviewing research articles, supporting training and supervising of trainee clinical scientists, and plays an active role in education and assessment.

CME

Quality Indicators in Barrett's Endoscopy: A Quest for the Holy Grail

27 October 2025

Factors associated with upper GI cancer occurrence after endoscopy

24 February 2025

Masterclass: Achalasia - Beyond the Basics

05 November 2024

- Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of Esophageal Motility Disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;27:160-174.

- Suzuki H. The application of the Rome IV criteria to functional esophagogastroduodenal disorders in Asia. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;23:325-333.

- Lindvall Dahlgren C, Wisting L, Rø Ø. Feeding and eating disorders in the DSM-5 era: a systematic review of prevalence rates in non-clinical male and female samples. J Eat Disord 2017;5:56.

- Avalos DJ, Robles A, Paik IJ, Hershman M, McCallum RW. Nausea, belching, and rumination disorders. In: Rao SSC, Lee YY, Ghoshal UC (eds). Clinical and basic neurogastroenterology and motility. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 2020: 293-304.

- Tucker E, Knowles K, Wright J, Fox M. Rumination variations: aetiology and classification of abnormal behavioural responses to digestive symptoms based on high-resolution manometry studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2012;37:263-274.

- Murray HB, Juarasico AS, Di Lorenzo C, Drossman DA, Thomas JJ. Diagnosis and treatment of rumination syndrome: a critical review. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:562-578.

- O'Brien M, Bruce B, Camilleri M. The rumination syndrome: clinical features rather than manometric diagnosis. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1024-1029.

- Vachhani H, Ribeiro B, Schey R. Rumination syndrome: recognition and treatment. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2020;18:60-68.

- Rosen R, Rodriguez L, Nurko S. A study using high resolution esophageal manometry with impedance. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017;29:1-16.

- Barba E, Burri E, Accarino A, et al. Biofeedback-guided control of abdominothoracic muscular activity reduces regurgitation episodes in patients with rumination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015;13:100-106.

- Barba E, Accarino A, Soldevilla A, Malagelada J, Azpiroz F. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of biofeedback for the treatment of rumination. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1007-1013.

- Thomas JJ, Murray HB. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of adult rumination behavior in the setting of disordered eating: a single case experimental design. Int J Eat Disord 2016;49:967-972.