Author:

Darren Fernandes, ST6

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer in the UK. In 2014, there were over 150,000 people living with cancer in the East Midlands with nearly one fifth of these having CRC. Survival rates for CRC depend on the stage at diagnosis. However, for all stages, survival is increasing. Whilst an increase in survival rates is a significant achievement, there are unintended negative consequences associated with this. As a result of having CRC and undergoing the associated treatments, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgery, the quality of life of those concerned can potentially be greatly affected. The subsequent effect of this is increased survivorship burden, resulting in a number of physical symptoms that includes gastrointestinal problems such as excessive wind, urge, diarrhoea and incontinence.

In the UK, CRC patients are followed up post treatment in secondary care for a period of 3 years, in accordance with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guideline NG151. The focus of these consultations tends to be on cancer recurrence and so most patients are not asked about possible side effects systematically and when they acknowledge that they do have problems, they do not receive many of the treatments that might be effective and are not investigated appropriately. This can have a detrimental effect on their quality of life (QoL).

In 2020, we aimed to start a specialist clinic at the United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust (ULHT) with the purpose of managing patients who had developed troubling bowel symptoms as a consequence of their CRC treatment. Patients were able to be referred locally and regionally via their CRC surgeons, nurse specialists or oncologists. Unfortunately, the timing of opening this clinic coincided with the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. This led to the clinic being postponed by 6 months. Another problem that arose as a result of the pandemic was that patients could no longer be seen face-to-face as a significant proportion of this group were considered at high risk and advised to shield. This required the clinic to change to a virtual telephone clinic. However, in hindsight, this proved to be beneficial as patients were not needing to make arduous journeys to hospital which would often require them to fast for 24 hours due to their debilitating bowel symptoms.

The clinic also suffered from a lack of referrals in the early stages. This again was partly related to the pandemic, where specialist nurses were having no time to make referrals or were being redeployed to other clinical areas, as well as due to a lack of awareness of our service. This required the clinician leading the clinic to arrange a number of meetings with various teams and stakeholders. Presentations were given at the Lincolnshire Integrated Care Board, at the East Midlands Cancer Alliance and to the colorectal team at ULHT. This publicising led to a significant increase in referrals as more specialists were aware of the clinic and how it could help improve the overall quality of life of patients under their care.

Outcomes

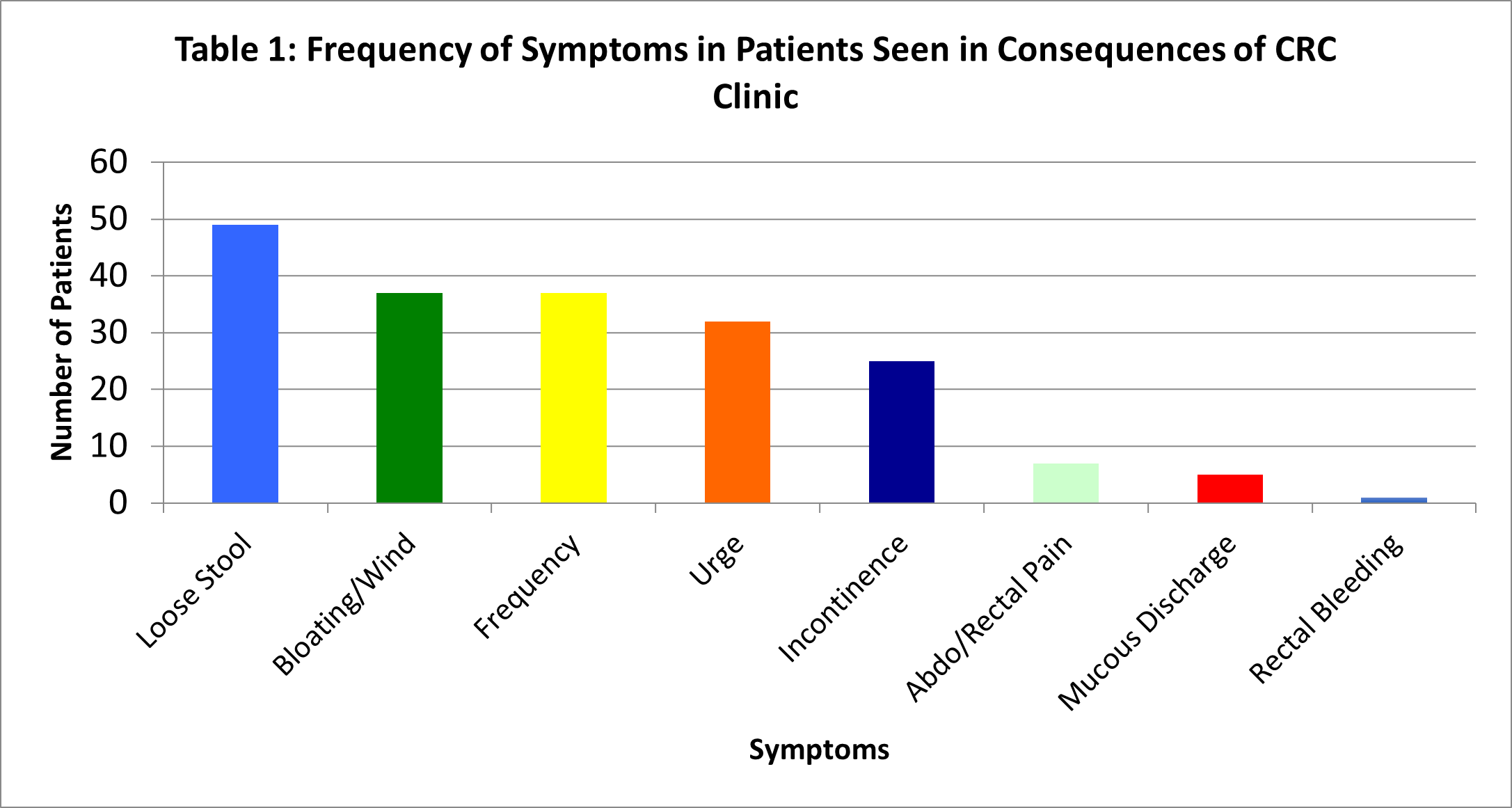

80 patients (37 male, 43 female), median age 69 (range 40-89) were reviewed between October 2020 to February 2023. The mean duration of symptoms was 31 months (range 2 to 134). All had been diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Previous treatment included surgery (n=38), surgery + chemotherapy (n=19), surgery + radiotherapy (n=4), surgery + radiotherapy + chemotherapy (n=14) and radiotherapy + chemotherapy (n=5). Patients’ symptoms pre-referral and after treatment were assessed objectively using the gastrointestinal symptoms rating scale (GSRS), with a significant improvement in scores following investigation and treatment. 8 different symptoms (Table 1) were identified in patients (loose stool (n=49), bloating/wind (n=37), frequency (n=37), urge (n=32), incontinence (n=25), abdominal/rectal pain (n=7), mucous discharge (n=5) and rectal bleeding (n=1)).

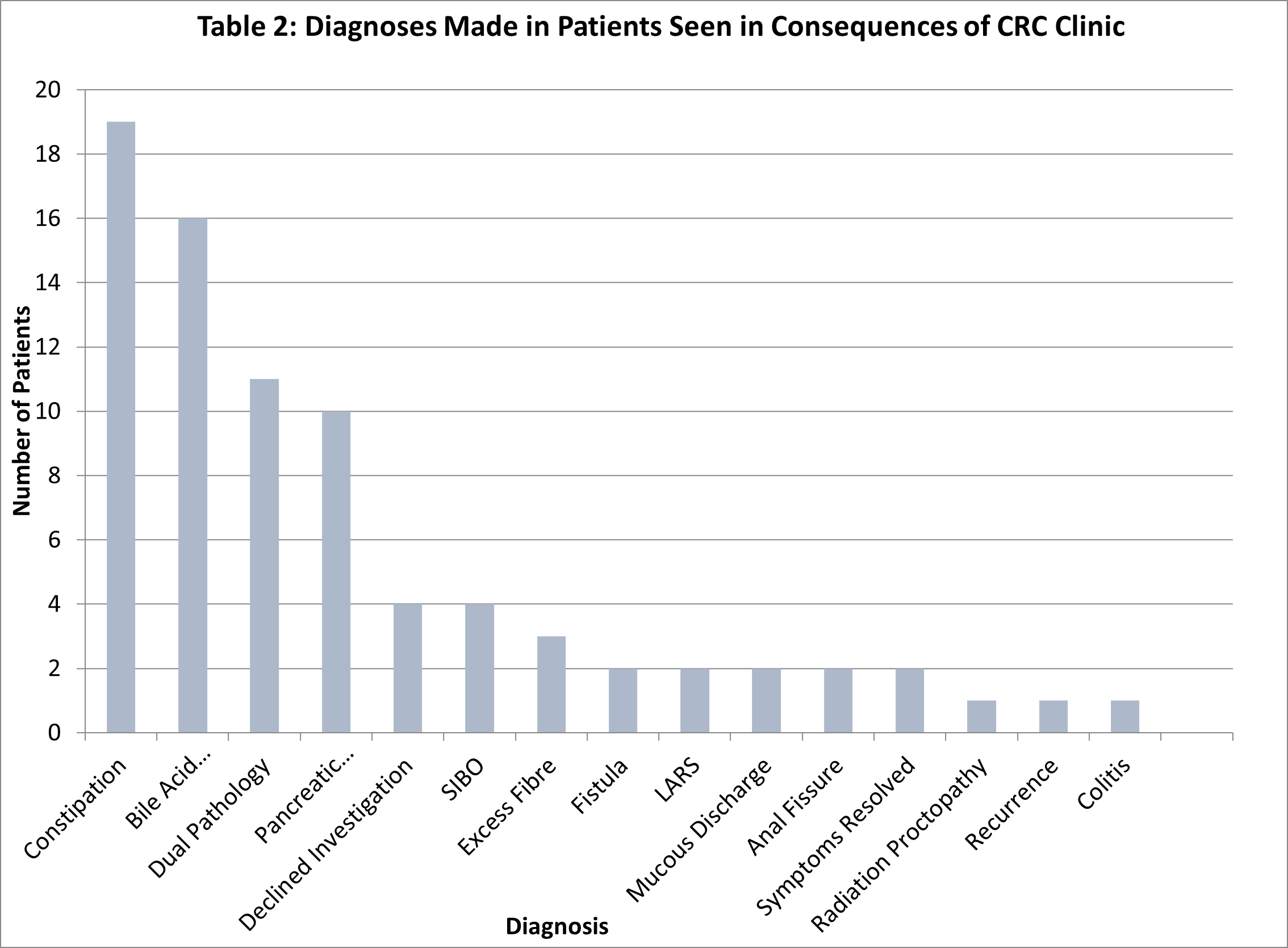

Diagnoses made are shown in Table 2. The mean overall package of care cost £1057.73 (range £86.83 - £1778.49) / patient.

Conclusion

In most patients referred to our specialist clinic, one or more causes for their symptoms were identified and subsequent treatment frequently led to a dramatic improvement in symptoms. We have therefore shown the importance of having a designated specialist Gastrointestinal clinic aimed at managing the side effects of CRC. However, this clinic can also help patients who are suffering with symptoms as a consequence of treatment for other cancers too. At a time when the NHS is in crisis and the priority for trusts is to focus on emergency and elective care whilst saving money, seeking funding from hospital service leads and managers can prove to be difficult. However, Gastroenterologists interested in setting up a similar service can use the statistics of future burden relating to this patient group and highlight how running a service like ours not only improves patients’ quality of life but is also cost effective and reduces the need for unnecessary investigations such as CT scans or endoscopic procedures in the long term. We would also advise interested Gastroenterologists to work alongside their colorectal cancer surgeons and nurse specialists as well as any practitioners running a late effects service so that the service can be tailored to meet the needs of their patients. In addition, we would encourage providing remote consultations, where possible and based on patient preference, as this proved to be more convenient for patients. Another useful inclusion for developing any potential service would be to have a patient and public involvement group. Although we did not have one specifically for when we set up our service, the lived experiences of local patients affected by cancer will also help to shape the clinic and make it as helpful to this cohort of patients as it can be.

Read More