Learning Points

- A clinical diagnosis of rumination syndrome should be considered in patients presenting with recurrent effortless post-prandial regurgitation of undigested food without nausea

- Concurrent oesophageal manometry with impedance monitoring after a test meal can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis

- Behavioural modification techniques, such as diaphragmatic breathing and biofeedback, to counteract habitual contractions of the intercostal and abdominal wall musculature are highly efficacious in improving symptoms and are the mainstay of treatment

Case Study

A woman aged 24 years was admitted to hospital with a history of weight loss and recurrent vomiting. She described effortless regurgitation of undigested food in the post-prandial period. There was no history of nausea or retching. The patient often re-swallowed the regurgitated material. Physical examination was unremarkable aside from a low BMI of 15.7 kg/m2 and weight of 42.9 kg.

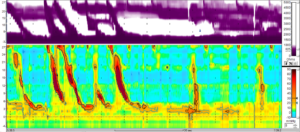

She had previously been investigated by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in another hospital, for which the findings were normal. Repeat endoscopy at the time of admission was also normal. The clinical picture was in keeping with rumination syndrome and, therefore, high-resolution impedance manometry was performed. Following a test meal, the patient demonstrated abdominal straining with retrograde liquid flow and regurgitation (Figure 1), which supported the diagnosis.

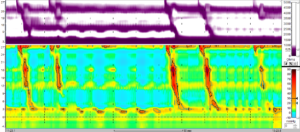

Management involved nutritional support with post-pyloric feeding, initially with a percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy and later with a surgical jejunostomy. In addition, she underwent manometry-guided biofeedback to correct the ruminating behaviour (Figure 2). At a clinic review at 6 months, she had gained weight, reaching 51.0 kg, and showed improvement in symptoms sufficient to have the jejunostomy removed at 11 months.

Introduction

Rumination syndrome is a poorly understood chronic upper-gastrointestinal motility disorder that can affect people of any age. It is often misdiagnosed due to limited awareness of the condition. Consequently, many patients undergo repeated invasive investigations and see multiple physicians, and the correct diagnosis is frequently delayed by several years following the onset of symptoms. Symptoms might arise following acute infections, surgery, psychological stress and major life events but, in most cases, there is no clear precipitant.

Clinical features

Rumination, derived from the Latin ruminare, is literally translated as "to chew the cud". It has long been recognised in animals, such as cattle, that regurgitate, rechew and reswallow food as an essential part of the digestive process.1

Despite advances in motility diagnostics, rumination syndrome remains a predominantly clinical diagnosis, based on interpretation of a detailed history.2 The pathognomonic diagnostic clinical features are repetitive, effortless regurgitation of recently ingested food into the mouth followed by rechewing and reswallowing or expulsion of the food bolus.3 These symptoms often occur within minutes of eating but can occur up to 2 hours after oral intake. Patients frequently regurgitate recognisable undigested food, which may retain a pleasant taste. The effortless regurgitation events are not usually preceded by nausea, and generally cease when the regurgitated material becomes acidic. These clinical features form the basis of the Rome IV diagnostic criteria.3

Differential diagnosis in adult patients can be complex, especially in female adolescent patients, in whom bulimia nervosa is often considered. Gastroparesis is another common misdiagnosis of rumination syndrome. Despite there being some overlapping features in these disorders, there are subtle differences in clinical presentation that help differentiation. For example, patients with bulimia nervosa who intentionally induce vomit seldom reswallow food. In gastroparesis, the temporal relationship is important because the vomiting tends to occur several hours after eating and is often associated with preceding nausea and retching. If, however, there are clinical concerns about the possibility of an eating disorder, a psychiatric opinion should always be sought.

Investigations

Rumination syndrome is an acquired behavioural disorder. However, when there is diagnostic uncertainty and/or poor patient acceptance of a clinical diagnosis of rumination syndrome, motility testing can be useful.

In rumination syndrome, habitual intercostal and anterior abdominal wall muscular contractions during the post-prandial period have consistently been observed and are thought to reflect the underlying mechanism of this disorder. These subconscious contractions increase intra-abdominal and gastric pressures while simultaneously relaxing the lower oesophageal sphincter, hence promoting regurgitation into the oropharynx.

Following provocation with a solid test meal, an abrupt rise occurs in intra-gastric pressure (to 25–30 mm Hg) followed by retropulsion of contents through the lower oesophageal sphincter within 10 seconds of the strain. High-resolution oesophageal impedance manometry can be used to visualise this change (Figure 1). The impedance monitoring is important to demonstrate the retrograde flow of regurgitated material through the lower oesophageal sphincter; this feature would not be detectable on oesophageal manometry studies alone. Typically, concurrent manometry and impedance studies are carried out for up to 3 hours following the test meal.

A limitation of combined impedance manometry is that as rumination syndrome is a behavioural disorder that patients are often able to control and suppress subconsciously in social contexts or when distracted. Thus, the diagnostic value of a 3 hour catheter-based study might be limited. Longer recording over 24 hours with ambulatory oesophageal pH and impedance monitoring has been suggested to help the diagnosis of rumination syndrome by specifically analysing the early post-prandial period for proximal reflux and regurgitation events.4 Use of this ambulatory study in addition to stationary post-prandial impedance manometry could increase the diagnostic yield.

Management:

Optimising doctor–patient interaction

Once the diagnosis is recognised, one of the most important aspects of treatment is an effective doctor–patient interaction. A detailed explanation to provide clear understanding of the diagnosis and the mechanisms of symptoms should be provided along with reassurance. Patients should be informed in an empathetic fashion that the regurgitation is caused by an involuntary habit leading to subconscious tension of the abdominal muscles. This type of consultation along with a positive clinical diagnosis is often of considerable relief to patients and their families, and in many cases is the only treatment required.

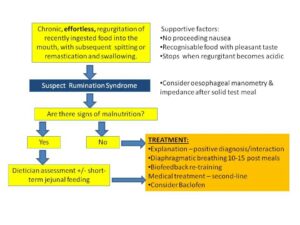

The mainstays of treatment include behavioural and medical interventions aimed at reducing the number of habitual abdominal contractions. At the point of diagnosis, many patients with severe rumination syndrome are often unable to retain any food or liquid and, therefore, are at risk of dehydration and malnutrition; weight loss can be a prominent clinical feature. As outlined in the case study presented, a period of short-term jejunal tube feeding might be required to address related malnutrition.5 However, escalation to jejunal tube feeding should not be required longer term, as once the syndrome is recognised it usually responds well to specific behavioural and medical interventions targeted at the underlying pathophysiology (Figure 3). Patients with underlying weight loss often require a multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterology, dietetics, nutrition support and clinical psychology.5,6 This strategy enables efficient use of medications, the ability to transition gradually from supplemental to oral feeds, close monitoring of nutritional and hydration status and focused, intensive work on the behavioural aspects of rumination syndrome.6

Behavioural interventions

Diaphragmatic breathing

Open-mouth diaphragmatic breathing during the post-prandial phase is recommended as the first-line approach for treating rumination syndrome due to its efficacy, ease, and low cost of administration.2 Numerous studies have shown the benefit of this technique in reducing regurgitation events. The postulated mechanism is that diaphragmatic breathing relaxes the abdominal wall, operating as a competing response to habitual contraction.2 One of the main advantages is that diaphragmatic breathing is easy to learn and can be demonstrated to a patient during a clinic attendance.

In brief, the patients are instructed to sit in a relaxed position, with one hand placed on the chest, and the other hand over the upper abdomen. Patients are then taught to maintain a still position of the hand on the chest wall, whilst the hand on the abdomen should be observed to rise and fall with each breath. This technique should be practised by the patient following all meals for 10–15 minutes and after any episode of regurgitation beyond that time. The aim of this learning process is to subconsciously make diaphragmatic breathing the natural breathing pattern in the post-prandial period and correct the habitual intercostal and abdominal wall contractions. This intervention can be implemented by any suitably trained health-care professionals (e.g. gastroenterologists, nurse specialists, speech therapists, physiotherapists and clinical psychologists), depending on local availability and expertise.

Biofeedback

As in several other functional gastrointestinal disorders, biofeedback can be a very helpful tool to promote behavioural modification and has been shown to improve symptom control.7,8 This process visually demonstrates the habitual abdominal contractions to the patient via either electromyography or manometry displays. From our clinical experience, even a brief period of this intervention at directly following an impedance manometry study, with or without a demonstration of diaphragmatic breathing, can significantly improve symptoms and clinical outcomes.

Medical interventions

There are very few studies of medical interventions for rumination syndrome. Baclofen is the only medication that has shown some promise.9,10 It is thought to reduce post-prandial flow events by increasing the resting pressure of the lower oesophageal sphincter and by potentially reducing transient relaxations. However, its use may be limited by its sedating side-effect profile. Currently, this treatment is recommended only for patients who do not significantly improve with behavioural interventions.2

Surgical interventions

In patients refractory to behavioural and medical treatments, the role of surgical intervention in the form of a Nissen fundoplication remains unclear. The literature on this intervention in rumination syndrome is limited to a small case series (n=5)11 and case reports.12

Conclusions

Rumination syndrome is a treatable functional gastroduodenal behavioural disorder with distinctive clinical features. It is often undetected and untreated due to lack of awareness amongst health-care professionals. Early recognition of the clinical features and commencement of treatment is vital to prevent severe consequences, including malnutrition, and impaired quality of life.

Figure 1. Rumination syndrome demonstrated on high-resolution

oesophageal manometry and impedance monitoring

Shortly after consuming a small cereal portion, normal solid swallows were followed by rumination behaviour, observed as increases in abdominal and oesophageal pressures.

Figure 2. Combined oesophageal manometry with impedance demonstrating

normalisation of rumination behaviour shortly after eating

following biofeedback and diaphragmatic breathing Figure 3. Summary of the clinical diagnosis and

Figure 3. Summary of the clinical diagnosis and

management of rumination syndrome

Author Biographies

Dr Dipesh Vasant

Consultant Gastroenterologist, Neurogastroenterology Unit, Wythenshawe Hospital, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust.

Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Manchester

Dr Ben Disney

Consultant Gastroenterologist, University Hospital Coventry

CME

Masterclass: Narcotic Bowel Syndrome

10 February 2025

Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction

28 October 2024

Clinical updates on the diagnosis and management of functional dyspepsia

02 January 2024

- Disney B, Trudgill N. Managing a patient with rumination. Frontline Gastroenterol 2013;4:232–36.

- Murray HB, Juarascio AS, Di Lorenzo C, Drossman DA, Thomas JJ. Diagnosis and treatment of rumination syndrome: a critical review. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:562–78.

- Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1380–92.

- Nakagawa K, Sawada A, Hoshikawa Y, et al. Persistent postprandial regurgitation vs rumination in patients with refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: identification of a distinct rumination pattern using ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:1248–55.

- Paine P, McMahon M, Farrer K, Overshott R, Lal S. Jejunal feeding: when is it the right thing to do? Frontline Gastroenterol Published Online First: 25 November 2019. doi: 10.1136/flgastro-2019-101181.

- Green AD, Alioto A, Mousa H, Di Lorenzo C. Severe pediatric rumination syndrome: successful interdisciplinary inpatient management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2011;52:414–18.

- Barba E, Accarino A, Soldevilla A, Malagelada J-R, Azpiroz F. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of biofeedback for the treatment of rumination. American J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1007–13.

- Barba E, Burri E, Accarino A, et al. Biofeedback-guided control of abdominothoracic muscular activity reduces regurgitation episodes in patients with rumination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:100–06.e1.

- Blondeau K, Boecxstaens V, Rommel N, et al. Baclofen improves symptoms and reduces postprandial flow events in patients with rumination and supragastric belching. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:379–84.

- Pauwels A, Broers C, Van Houtte B, Rommel N, Vanuytsel T, Tack J. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study using baclofen in the treatment of rumination syndrome. American J Gastroenterol 2018;113:97–104.

- Oelschlager BK, Chan MM, Eubanks TR, Pope CE, Pellegrini CA. Effective treatment of ruminations with Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:638–44.

- Fullerton DT, Neff S, Getto CJ. Persistent functional vomiting. Int J Eat Disord 1992;12:229–33.