Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is also known to have extra-intestinal manifestations, particularly rheumatological complications (1). Clinicians need to recognise these manifestations as early diagnosis and treatment leads to better patient outcomes. Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a term used to refer to a group of inflammatory arthritides that is associated with the HLA-B27 gene including axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA), reactive arthritis (ReA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-related arthritis (Table 1). The SpA spectrum includes involvement of the spine (axial disease), peripheral joints (peripheral SpA), areas where tendons and ligaments attach to bone (enthesitis) and digits (dactylitis).

Spondyloarthropathies (HLA-B27 associated disease) |

Non-radiographic axSpA (MRI positive, X-ray negative changes in spine) Radiographic axSpA (ankylosing spondylitis with both MRI and X-ray changes) |

|

|

Crohn’s disease Ulcerative colitis |

|

|

|

Rheumatological manifestations of spondyloarthritis |

Sacroilitis (inflammation in sacroiliac joints) Syndesmophytes (bony growth in spinal ligament) Osteitis (inflammatory lesion in bone) |

Monoarthritis (single joint involvement, consider septic arthritis in differential) Oligoarthritis (2-4 joints involved in an asymmetrical distribution) Polyarthritis(more than 4 joints involved, also seen in enteropathic arthritis) |

|

|

Other extra-intestinal manifestations of spondyloarthropathies |

|

|

|

Table 1. The classification, rheumatological and extra-intestinal manifestations of spondyloarthropathies

Enteropathic arthritis is an umbrella term used to describe rheumatological conditions that have a gastrointestinal association. An example of enteropathic arthritis is the link between SpA and IBD (2). In axSpA, the prevalence of IBD which is an extra-musculoskeletal manifestation (EMM) of the condition is 7%. However, if looking at subclinical inflammatory bowel disease, the prevalence is much higher at 50%. Risk factors include a family history and an elevated CRP (3). As with subclinical gut inflammation, there is also a subclinical joint inflammation that can be observed in patients with IBD. Interestingly, 50% of patients who go on to be diagnosed with IBD initially present with musculoskeletal symptoms and arthralgia (4).

Clinical presentation – screening and questions

AxSpA should be suspected in patients that have lower back pain before the age of 40 years. The prevalence of axSpA is 1 in 200 of the population and in 5% of patients with chronic back pain. The main symptoms are inflammatory joint and back pain (5). These symptoms include: pain and swelling in joints, alternating buttock pain and pain that wakes the patient up at night, particularly in the second half of the night. The symptoms often get better with movement and with using non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Peripheral spondyloarthritis is suspected in patients whose symptoms are predominantly in their upper and lower limb joints. The symptoms again include pain/swelling of joints as well as tendons particularly at sites of insertion into bone, also known as enthesitis (6). There is also an association with uveitis and psoriasis.

There are many useful screening tools such as the National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society (NASS) symptom checker and the Spondyloarthritis Diagnostic Evaluation (SPADE) tool (7) that can be utilised by patients and clinicians to identify symptoms correctly and determine the need for a rheumatology referral. The NASS symptom checker is easily accessible online and is very straightforward to use. It consists of eight questions (Table 2) completed by the patient. Based on this, a calculation is made on how likely it is that the patient’s back pain may be due to axSpA. This will lead to referral guidance which can be brought to the GP or physiotherapist to aid onward referral to rheumatology. The NASS symptom checker can be displayed in the GP and specialist clinic waiting areas or be sent to patients to be completed (Supplementary Figure 1).

Question | Answer (Yes/No) |

Did your back pain start before the age of 40? | Yes/No |

Did your back pain develop gradually? | Yes/No |

Has your back pain lasted more than 3 months? | Yes/No |

Do you experience stiffness in your back in the morning for at least 30 minutes? | Yes/No |

Does your back pain improve when you move around? | Yes/No |

Does your back pain improve when you rest? | Yes/No |

Do you have back pain in your buttocks, which moves from one buttock to the other? | Yes/No |

Do you wake in the second half of the night because of your back pain? | Yes/No |

Table 2. The National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society (NASS) Symptom Checker Questionnaire that can be completed by patients with suspected axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). Available at http://www.actonaxialspa.com/symptoms-checker/

Investigations

When evaluating rheumatological manifestations in IBD, tests that would be useful to request include blood tests looking at inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) as well as a HLA-B27 test. Other investigations such as rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP are useful in diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis whilst if lupus was a differential that needed to be excluded, ANA would be a useful investigation. If axSpA is suspected, imaging such as X rays of the affected peripheral and sacroiliac (SI) joints as well as MRI scan of the whole spine and SI joints would aid in reaching a diagnosis (8). X-rays are useful to look for radiographic changes of axSpA. MRI is particularly useful in identifying early inflammatory lesions in the spine before changes appear on X-rays. In patients with peripheral SpA, in addition to blood tests, imaging of the peripheral joints with ultrasound or MRI may be useful to look for evidence of joint or tendon inflammation. In cases of swollen joints, joint aspiration may help differentiate between inflammatory arthritis and other causes, such as septic arthritis or crystal arthropathies (eg. gout or pseudogout).

Treatment

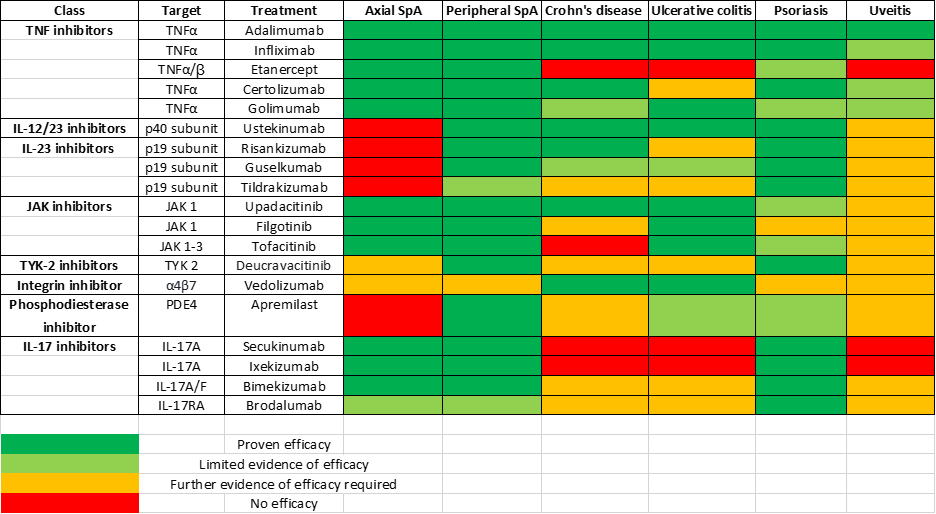

The primary goal for treatment is to ensure the optimal patient outcome through a multidisciplinary approach (9). For example, having combined clinics between rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, and primary care and community physiotherapists ensures that in addition to the arthritis, the patient’s EMMs are also treated. It is important that EMMs are taken into account when choosing a treatment for spondyloarthritis as there will be different effects from biologic and small molecule agents. With regards to the use of NSAIDs in IBD, it is not clear whether they could precipitate, worsen or prolong a flare. A 2022 American study suggested that the link between NSAID use and IBD flares could be due to residual bias so a discussion with the patient that follows a shared decision-making structure would be beneficial prior to treating with NSAIDs (10). Conventional DMARDS such as Methotrexate, Sulfasalazine and Azathioprine may be beneficial for peripheral arthritis. Short term steroids could be beneficial for both active peripheral arthritis and IBD especially during flares of disease. If there is an indication for biologics, anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies can be used for both axial and peripheral disease (11). Other biologics targeting IL-12/23 may also be considered based on the clinical scenario, an example biologic is Ustekinumab as this is useful in treating psoriatic arthritis and IBD but not effective for SpA (12). IL-17 inhibitors, often used to treat spondyloarthritis, is not recommended in IBD as it may exacerbate IBD (13). Another class of medications includes Janus Kinase inhibitors (JAKi) which are used in the management of enteropathic arthritis and can also be used in IBD if used at higher doses (14). However, it is important to note that there has been concerns about the increased risk of cardiovascular events and thrombosis associated with their use and so the risks need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis (15). Table 3 shows the overlap of treatment with IBD, rheumatological and other extra-intestinal conditions.

Table 3. The overlap of treatment with biologic and targeted synthetic disease modifying drugs (DMARDs) in IBD and other extra-intestinal manifestations.

Discussion

The association between IBD and rheumatological manifestations underscores the need for a comprehensive joined up management of these patients (16). Early recognition and treatment of IBD-related arthritis can improve overall outcomes and quality of life. While monitoring gastrointestinal symptoms, it is important to stay vigilant for joint pain, stiffness and swelling, as this can significantly affect patient outcomes and well-being if not assessed and treated early (17). The awareness and understanding of extra-intestinal manifestations can help with the choice of drugs including biologics in IBD.

Conclusion

Rheumatological manifestations associated with IBD can complicate management and adversely impact patients’ quality of life. Clinicians must remain aware of the potential issues and advocate for a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Timely interventions can mitigate complications and enhance overall care for patients with IBD.

Summary

3 key points for practising clinicians:

- Recognise the spectrum of rheumatological conditions that are associated with IBD, including axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis.

- Refer early to Rheumatology if IBD patients have rheumatological manifestations using patient or clinician completed symptom checkers and referral pathways.

- Effective treatment of patients with IBD related rheumatological manifestations require multidisciplinary care and collaboration including gastroenterology, rheumatology and physiotherapy teams.

Declaration of conflicts of interests

Nikhita Joseph - none

Antoni Chan - speaker bureaus with Novartis, UCB, Lilly, Abbvie, Janssen. Advisory boards with Novartis, UCB, Amgen, Janssen.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. QR code for the NASS symptom checker questionnaire that can be completed by patients with suspected axSpA.

Author Biographies

Dr Nikhita Joseph, MBChB, Foundation Year One Doctor, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Nikhita Joseph is a Foundation Year One (FY1) Doctor at the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, UK. She graduated from the University of Birmingham in 2024. During medical school, she developed an interest in Rheumatology and participated in audits with a focus on biologic therapy. In addition to clinical training, she has a passion for research and has been involved in quality improvement projects within the hospital to identify areas of improvement to achieve better patient outcomes. She hopes to pursue a career in Rheumatology or General Practice.

.jpg)

Prof Antoni Chan, MBChB, FRCP, PhD, Professor of Rheumatology and Consultant Rheumatologist and Clinical Lead, University Department of Rheumatology, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, UK

Antoni Chan is Consultant Rheumatologist and Clinical Lead in Rheumatology at Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust, UK. His research interest is in the use of data, informatics and artificial intelligence (AI) to improve diagnosis and treatment of rheumatic conditions. Working with the University of Reading, he has been co-applicant for two large grants from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) for the study of AI for early diagnosis of inflammatory arthritis. His team were selected for the National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society (NASS) Aspiring to Excellence Award. He received the Patient Choice Award for Best Care by a Rheumatologist and Gold Changemaker Award in the Houses of Parliament, UK. He is Trustee and Medical Advisory Board Member of NASS. He is a full member of ASAS and GRAPPA. He led the GP educational pogramme (RheumACaN) with his team which won the national British Society for Rheumatology Best Practice Award in 2024.

CME

IBD Surveillance Colonoscopy – This is how I do it

03 December 2024

SSG Digest This! Simulated multi-disciplinary meeting: IBD scenarios

16 October 2024

1. Wang C-R, Tsai H-W. Seronegative spondyloarthropathy-associated inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jan 21;29(3):450–68.

2. Kumar A, Lukin D, Battat R, Schwartzman M, Mandl LA, Scherl E, et al. Defining the phenotype, pathogenesis and treatment of Crohn’s disease associated spondyloarthritis. J Gastroenterol. 2020 Jul;55(7):667–78.

3. Chmielińska M, Felis-Giemza A, Olesińska M, Paradowska-Gorycka A, Szukiewicz D. The failure of biological treatment in axial spondyloarthritis is linked to the factors related to increased intestinal permeability and dysbiosis: prospective observational cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2024 Aug;44(8):1487–99.

4. Redeker I, Siegmund B, Ghoreschi K, Pleyer U, Callhoff J, Hoffmann F, et al. The impact of extra-musculoskeletal manifestations on disease activity, functional status, and treatment patterns in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from a nationwide population-based study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020 Nov 21;12:1759720X20972610.

5. Rios Rodriguez V, Duran TI, Torgutalp M, López-Medina C, Dougados M, Kishimoto M, et al. Comparing clinical profiles in spondyloarthritis with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis: insights from the ASAS-PerSpA study. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2024 May 22;8(2):rkae064.

6. Akrapovic Olic I, Vukovic J, Radic M, Sundov Z. Enthesitis in IBD patients. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 3;13(15).

7. National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society. NASS Symptom Checker Questionnaire [Internet]. Act on Axial SpA. [cited 2024 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.actonaxialspa.com/symptoms-checker/

8. Ergenc I, Kani HT, Gundogmus CA, Ergelen R, Afsar Satis N, Ekinci G, et al. Presence of axial spondyloarthritis associated sacroiliitis and structural changes on MR enterography: A direct comparison with sacroiliac joint MRI. Clin Imaging. 2022 Dec;92:19–24.

9. National Axial Spondyloarthritis Society. Early recognition of axial spondyloarthritis(axial SpA) in patients with inflammatorybowel disease (IBD) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Nov 3]. Available from: https://www.actonaxialspa.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/5620-NASS-IBD-in-diagnosis-of-AS_Digital.pdf

10. Cohen-Mekelburg S, Van T, Wallace B, Berinstein J, Yu X, Lewis J, et al. The Association Between Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Exacerbations: A True Association or Residual Bias? Am J Gastroenterol. 2022 Nov 1;117(11):1851-1857.

11. Cozzi G, Scagnellato L, Lorenzin M, Savarino E, Zingone F, Ometto F, et al. Spondyloarthritis with inflammatory bowel disease: the latest on biologic and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023 Aug;19(8):503–18.

12. Guillo L, D’Amico F, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ustekinumab for Extra-intestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Literature Review. J Crohns Colitis. 2021 Jul 5;15(7):1236–43.

13. Onac IA, Clarke BD, Tacu C, Lloyd M, Hajela V, Batty T, et al. Secukinumab as a potential trigger of inflammatory bowel disease in ankylosing spondylitis or psoriatic arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Nov 3;60(11):5233–8.

14. Shahid Z, Brent LH, Lucke M. Enteropathic Arthritis. [Updated 2024 Apr 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.[cited 2025 Jan 10] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594239/

15. Harrington R, Harkins P, Conway R. Janus Kinase Inhibitors in Rheumatoid Arthritis: An Update on the Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib, Baricitinib and Upadacitinib. J Clin Med. 2023 Oct 23;12(20):6690.

16. Ibáñez Vodnizza SE, De La Fuente MPP, Parra Cancino EC. Approach to the Patient with Axial Spondyloarthritis and Suspected Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020 May;46(2):275–86.

17. Rios Rodriguez V, Sonnenberg E, Proft F, Protopopov M, Schumann M, Kredel LI, et al. Presence of spondyloarthritis associated to higher disease activity and HLA-B27 positivity in patients with early Crohn’s disease: Clinical and MRI results from a prospective inception cohort. Joint Bone Spine. 2022 Oct;89(5):105367.