Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most common cancer in the UK, and the second most common cause of cancer death in the UK, accounting for 10% of all cancer deaths.1

Understanding the tools available to aid in diagnosis and decision making is something that needs to be clear for any clinician dealing with signs or symptoms of suspected colorectal cancer.

Faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) is a quantitative test for the presence of altered blood in stools (haemoglobin and its degradation products) and has a high sensitivity and superior positive predictive value for the detection of CRC compared to symptoms alone. The BSG/ACPGBI and NICE guidelines have identified the threshold of 10 µg Hb/g as being the relevant clinical cut-off for investigation2 and a FIT below threshold conveys a low risk of CRC.3

This BSG web education series discusses four cases from which key learning points are highlighted for anyone involved in FIT interpretation.

Case 1

ES is a 20-year-old female who presents to her GP with PR bleeding for 1 month.

A FIT test is performed and returns at 100 µg Hb/g.

ES is referred on the urgent referral pathway and advised that she could have cancer. On receipt of the referral, she is triaged to have both a faecal calprotectin (FCP) and an urgent colonoscopy. The FCP returns raised at 1300 μg/g. The colonoscopy is in keeping with distal ulcerative colitis, confirmed on biopsy.

Learning points: Always consider checking FCP first in the young (under 50 years of age) presenting with bowel symptoms in primary and secondary care. NHS England have suggested it can be used up to the age of 60 in primary care.4 The main differentials in this situation are likely to be haemorrhoids or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rather than CRC. Although the incidence of CRC in patients under 50 is rising it still remains a relatively rare diagnosis.5

FIT is still a reliable test in patients with frank rectal bleeding.6 They do need to be counselled however, to sample a non-bloody stool, or to sample the end of the stool away from the blood. A FIT result of <10 μg Hb/g can also help identify those patients who could be investigated with sigmoidoscopy rather than full colonoscopy.7

Case 2

RW is a 79-year-old male with stage 4 chronic kidney disease, ischaemic heart disease and a previous stroke. He is bedbound and has carers visiting four times a day.

He presents to the GP with weight loss and constipation. He is deemed unfit for invasive investigations due to his multiple co-morbidities and frailty. The GP sends in an ‘advice and guidance’ request querying the utility of FIT in such a scenario.

Learning point: FIT is a triage tool designed, in the symptomatic population, to determine the relative urgency of investigation, or to provide reassurance that onward referral is necessary. It is not a useful tool if the patient is unfit for investigation. In this scenario, it is reasonable to declare a patient unfit for investigation. If a FIT is performed on a patient with extensive comorbidities and it is above threshold – it will arguably generate anxiety and inappropriate testing in an individual who will not receive any benefit from these tests.

Case 3

GC is a 69-year-old fit and well male. He presented to his GP with a 3-week history of change in bowel habit. On testing, he was found to have an iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) and a FIT of 8 μg Hb/g.

He underwent a colonoscopy on the urgent pathway which was normal.

He was subsequently reviewed in clinic and scheduled for an upper GI endoscopy.

Learning point: The FIT guidelines suggest that FIT be used for IDA within primary care to inform urgency of referral. The FIT sensitivity is 80.0% in patients with IDA compared with 89.0% in those with a combination of other symptoms,8 in other words, IDA does reduce the fidelity of FIT.

There is a slightly higher rate of upper GI cancer in patients with a positive FIT and a negative lower GI investigation,9 and it is important to remember to not solely rely on FIT if symptoms are persistent.

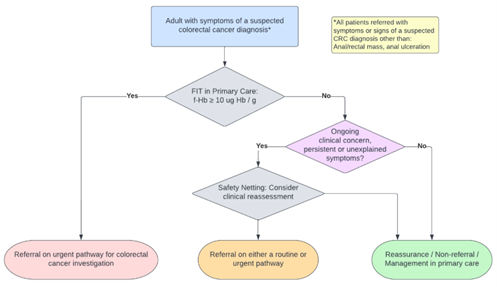

Figure 1: FIT guidelines pathway flowchart3

Case 4

KC is a 74year old female with a history of hypertension. She presents to her GP with a change in bowel habit possibly following initiation of beta-blockers. She is not anaemic on blood tests and her FIT is <10 μg Hb/g. Her GP asks her to return for a safety-netting appointment in 8 weeks’ time, at which point her haemoglobin remains normal and her FIT remains below threshold.

Her GP reassures her that further invasive testing is not necessary and instead a different anti-hypertensive treatment is suggested.

Learning point: It is very unlikely a patient will have CRC after 2 FIT tests below threshold. Data has suggested patients with two negative FIT tests have a colorectal cancer risk of <0.04%10 It is important however to use FIT as part of holistic assessment. If patients still have symptoms, then GPs still have the option for ongoing referral for further investigation (highlighted in the orange box in Figure 1).

Discussion

There is now ample data to support the use of FIT as a triage tool in patients with bowel symptoms. The NICE FIT study, a multicentre double-blinded study of 9822 patients demonstrated the risk around 0.2% in those with an undetectable FIT and 0.4% in those with FIT<10 µg Hb/g.11

The FIT guidelines3 describe how FIT enables triage of patients into three groups; those who require urgent referral on a suspected cancer pathway, referral via a routine pathway and significantly lower risk patients who may be potentially managed in primary care. The benefits of this include reducing unnecessary colonoscopy on symptomatic patients (80% in one study)12 which can instead be used to expand bowel cancer screening.

FIT has an acceptable miss rate whether used in primary care prior to referral or in secondary care following referral. It is important to remember that colonoscopy itself also has a false negative rate.13

Conclusion

The above cases highlight the considerable advantages of FIT testing when it comes to the management of patients with bowel symptoms in terms of identifying high risk patients or providing reassurance in low-risk patients. The current challenge is to provide evidence of optimal pathways for safety-netting patients with a FIT below threshold.

If utilised effectively it can be a powerful triage tool for clinicians in identifying patients at risk of colorectal cancer who would benefit from invasive investigation and provide an evidence-based approach to their care superior to symptoms alone.

Author Biographies

Dr Jabed F Ahmed

Jabed is a gastroenterology trainee registrar and a member of the BSG colorectal committee. He has an interest in advanced lower GI techniques and his research is in novel technologies to improve lower GI endoscopy.

Dr Edward Seward

Ed Seward trained in Edinburgh and has worked as a consultant gastroenterologist initially in east London before being appointed at University College London Hospital in 2014. As Endoscopy Lead in both hospitals he developed a sub-specialist interest in therapeutic Endoscopy as well as pursuing a passion for service improvement and redesign, which culminated in his appointment as a National Clinical Advisor for Endoscopy. He has been responsible for leading on (or contributing to) many innovations in service design such as straight to test, use of FIT in the colorectal diagnostic pathway, RAS clinics and colon capsule at home.

Ed specialises clinically in colonoscopy and large polyp removal, and his research interests currently include FIT, ESD, colon capsule and use of AI in the lower GI tract. He teaches extensively on these subjects, and is lead for the North Central London Endoscopy Academy.

CME

Masterclass - Colonic stents - who, when and where

02 September 2024

Colorectal Cancer Screening: An international perspective

25 June 2023

- “Bowel cancer statistics”. Cancer Research UK. Publication Date: 30 January 2024. URL: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer#heading-Zero

- “Quantitative faecal immunochemical testing to guide colorectal cancer pathway referral in primary care”. NICE. Publication Date: 24 Aug 2023. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg56/chapter/1-Recommendations

- Monahan KJ, Davies MM, Abulafi M, et al. Faecal immunochemical testing (FIT) in patients with signs or symptoms of suspected colorectal cancer (CRC): a joint guideline from the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) and the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG). Gut. 2022;71(10):1939-1962. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2022-327985

- “Faecal Calprotectin in Primary Care as a Decision Diagnostic for Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Irritable Bowel Syndrome”. NICE. Publication Date: 2 Oct 2013. URL: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg11/resources/endorsed-resource-consensus-paper-pdf-4595859614

- Tibbs RE, Benton SC. A service evaluation of the use of faecal immunochemical tests in symptomatic patients aged under 50 years presenting to primary care. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 2024;61(1):48-54. doi:10.1177/00045632231189386

- Hicks G, D'Souza N, Georgiou Delisle T, et al. Using the faecal immunochemical test in patients with rectal bleeding: evidence from the NICE FIT study. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23(7):1630-1638. doi:10.1111/codi.15593

- Digby J, Strachan JA, McCann R, Steele RJ, Fraser CG, Mowat C. Measurement of faecal haemoglobin with a faecal immunochemical test can assist in defining which patients attending primary care with rectal bleeding require urgent referral. Ann Clin Biochem. 2020 Jul;57(4):325-327. doi: 10.1177/0004563220935622

- Cunin L, Khan AA, Ibrahim M. FIT negative cancers: A right-sided problem? Implications for screening and whether iron deficiency anaemia has a role to play. Surg 2021; 19:27–32

- Van Der Vlugt M, Grobbee EJ, Bossuyt PM, et al. Risk of Oral and Upper Gastrointestinal Cancers in Persons with Positive Results from a Fecal Immunochemical Test in a Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2018;16(8):1237-1243.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.01.037

- Hunt N, Rao C, Logan R, et alA cohort study of duplicate faecal immunochemical testing in patients at risk of colorectal cancer from North-West EnglandBMJ Open 2022;12: e059940. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059940

- D’Souza N, Georgiou Delisle T, Chen M, et al. Faecal immunochemical test is superior to symptoms in predicting pathology in patients with suspected colorectal cancer symptoms referred on a 2WW pathway: a diagnostic accuracy study. Gut2021; 70:1130-1138

- Laszlo HE, Seward E, Ayling RM, et al. Faecal immunochemical test for patients with ’high-risk’ bowel symptoms: a large prospective cohort study and updated literature review. Br J Cancer 2022; 126:736–43

- Morris EJA, Rutter MD, Finan PJ, et alPost-colonoscopy colorectal cancer (PCCRC) rates vary considerably depending on the method used to calculate them: a retrospective observational population-based study of PCCRC in the English National Health ServiceGut 2015;64:1248-1256.