Learning points

- Duodenal varices are rare and clinically challenging causes of portal hypertensive bleeding associated with significant mortality; they require a high index of suspicion and multimodal diagnostic and therapeutic approaches

- Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection and band ligation remain first-line treatments for bleeding duodenal varices and may be further supported with endoscopic ultrasound-guided procedural intervention

- In patients where endoscopic management has failed, radiological intervention or surgery should be considered after appropriate venous mapping

Keywords

Duodenal varices, portal hypertension, variceal haemorrhage, cirrhosis, portal vein thrombosis

Background

The development of varices represents a state of altered portal circulatory haemodynamics in cirrhosis, which arises from increased vascular resistance to portal venous flow and secondary ‘dynamic’ responses of splanchnic vascular tone. These convert the portal venous pressure system from a low-pressure system (<1–5 mm Hg) to a higher-pressure system (>5 mm Hg). If the portal pressure gradient progresses to >10 mm Hg, portosystemic shunts develop with preferential venous drainage through collateral circuits. A hepatic–venous pressure gradient of >12 mm Hg is associated with increased risk of variceal haemorrhage, and a pressure gradient >20 mmHg is associated with a fivefold increase in mortality.1 Common sites for the development of varices are the oesophagus and gastric fundus. It is important to note that portal hypertension can occur in a variety of non-cirrhotic conditions.2

Duodenal varices have been reported in up to 40% of angiographic series,3 but duodenal variceal haemorrhage is rare, representing 0.4–1.0% of variceal bleeds seen complicating portal hypertension. However, duodenal variceal haemorrhage is often massive and life threatening, with mortality reported to be up to 40%.4

One-third of duodenal varices occur in the setting of extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis and the remainder are seen in the context of cirrhotic portal hypertension.5 Duodenal varices may form in cirrhotic patients after oesophageal variceal banding as the portal systemic pressure shifts, further opening portosystemic communications at ectopic sites. More than 75% of patients with duodenal varices have had prior oesophageal or gastric endotherapy. In these patients, the median time to presentation with duodenal varices is 2.3 (± 2.1) years.6

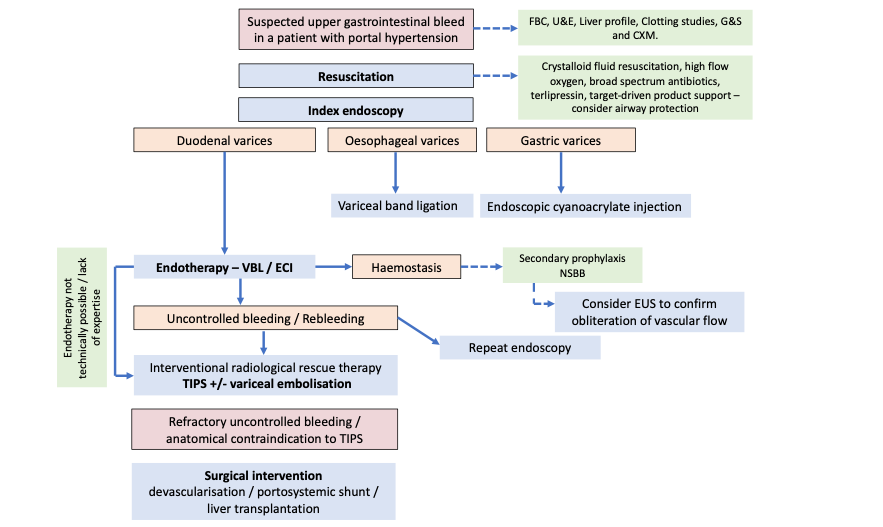

Duodenal varices can be difficult to visualise on endoscopy as they are often located submucosally and towards the serosal surface of the duodenal wall and are of short length and small diameter (Figure 1A); they may become more apparent as portal hypertension progresses. The identification of ectopic varices should prompt high-quality biphasic imaging in order to delineate the vascular anatomy of the liver and assess portal venous inflow and options for variceal therapy through endoscopic, radiological or surgical means. Use of non-selective beta blockers should be considered as first-line therapy, although data supporting this approach are limited. Bleeding from ectopic duodenal varices is a rare but serious complication, and comparative studies informing best approach to practice are lacking. Here we present our recommendations and practice for the management of duodenal variceal bleeding (Table 1, Figure 2).

Medical Management

Bleeding from varices at any site of portosystemic collateralisation is a related to a combination of variceal size, wall tension and transmural pressure. Patients with evidence of portal hypertension who present with acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage should be managed according to protocol algorithms outlined in the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines on variceal haemorrhage7 and the BSG and British Association for the Study of the Liver decompensated liver disease bundle.8 Evidence supports large-bore intravenous access and the administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics, splanchnic vasopressors and targeted blood product support with restrictive transfusion strategies in settings of non-massive variceal haemorrhage.

Endoscopic evaluation of duodenal varices requires a high index of suspicion and should always be considered in portal hypertensive patients where a source of bleeding has not been identified after careful inspection of the oesophagus and gastric fundus. In suspected ectopic variceal bleeding, intubation to the distal duodenum with push enteroscopy should be attempted, as duodenal varices are often located in the descending duodenum beyond the limit of standard procedural intubation. Further measures to evaluate suspected ectopic variceal bleeding include colonoscopy and either double-balloon enteroscopy or video-capsule endoscopy. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is a useful adjunctive technique to evaluate for the presence of duodenal collaterals and to guide therapeutic intervention.

Endoscopic Therapy

Where stigmata of active or recent haemorrhage (white nipple, red signs) are present, first-line treatment should be endoscopic variceal band ligation (VBL) or cyanoacrylate injection (ECI).9 VBL has been used with success in the management of duodenal variceal haemorrhage,10 but may be challenging depending on the location and size of the varices, visualisation, isolation of afferent vessels and engagement with the banding cap. and early rebleeding after endoscopic band ligation has been reported.11–13 ECI is efficacious in achieving haemostasis in patients with actively bleeding duodenal variceal haemorrhage and preventing early and long-term secondary haemorrhagic episodes (Figure 1B).14 ECI can be associated with complications, including retrograde expulsion of glue with systemic embolisation, which commonly affects the pulmonary vasculature, and local complications of ulceration, erosion and extrusion and reports of glue plugs forming a nidus for chronic infection.15

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided therapy

EUS-guided therapy is gaining increasing traction in the management of gastric and ectopic varices. Colour Doppler EUS has the advantage of being able to confirm obliteration of vascular flow. EUS-guided ECI of gastric varices was associated with significantly reduced rates of late rebleeding in a retrospective series (19% vs. 45% after treatment without EUS, p=0.0005).16 Coil embolisation guided by EUS has similar efficacy to EUS-guided ECI in the prevention of recurrent gastric variceal bleeding (95% vs. 91%) and significantly fewer complications (58 vs. 9%), predominantly by reducing those related to portosystemic glue embolisation.17 ECI may provide a scaffold against which smaller volumes of cyanoacrylate glue can be injected.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPSS) procedures establish communication between the portal and hepatic veins, which reduces the portal gradient and risk of variceal haemorrhage, and is efficacious for treatment of duodenal varices.18,19 TIPSS can be combined with transvenous obliteration of varices, either contemporaneously or in the setting of rebleeding.20 This procedure is associated with complications relating to encephalopathy (reported in up to 36% of patients), hepatic decompensation (Figure 1C), right heart failure and shunt occlusion, and patients should receive a comprehensive evaluation, detailed venous mapping, and specialist hepatological opinion prior to proceeding to radiological shunt procedures.

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration

Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration may be used to treat acute ectopic variceal haemorrhage refractory to endoscopic haemostasis or in patients who are deemed unsuitable for TIPSS. Retrograde selective cannulation of varices through a cannula sheath in the inferior vena cava can be used to access and occlude upstream varices, delineate the vascular anatomy and inject a sclerosant (Figure 1D).21,22

Surgical approaches to portal hypertension

Rarely, endoscopic and/or radiological measures fail or are technically not feasible. Revascularisation procedures and various non-selective portosystemic shunts have been successfully utilised to control variceal haemorrhage in carefully selected patients.23 Surgery for portal hypertension should be performed by experienced surgeons in specialised units and patients should have relatively preserved liver synthetic function.24,25 Liver transplantation remains the only modality that manages portal hypertension whilst simultaneously treating the underlying liver disease.

Conclusions

Duodenal varices are rare but challenging causes of portal hypertensive bleeding. They occur in settings of cirrhotic portal hypertension in addition to extrahepatic portal vein occlusion. Duodenal varices require a high index of suspicion in the setting of suspected variceal bleeding where oesophageal and gastric bleeding has been excluded. Endoscopic therapy remains the primary treatment modality for duodenal variceal haemorrhage. Detailed contrast-enhanced imaging is required to delineate splanchnic venous anatomy and plan rescue treatment. Second-line treatment strategies in settings where endoscopic therapy has failed should be undertaken in discussion with specialist hepatology centres, and include TIPSS, variceal obliteration, devascularisation and surgical shunt.

| Treatment modality | Endoscopic/interventional radiology | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection | Endoscopy | – Locally available – Good initial haemostasis

| – Rebleeding – Systemic glue embolisation – Portal vein occlusion – Formation of a septic nidus

|

| Variceal band ligation | Endoscopy | – Locally available – Good initial haemostasis | – Rebleeding – Band-induced ulceration – Technically challenging in some locations

|

| EUS-guided variceal endotherapy | Endoscopy | – Safe variceal puncture – Reduced volume of glue injection – Dynamic assessment of variceal flow | – Operator dependence – Limited availability

|

| Transjugular Intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | Interventional radiology | – Efficacious prevention of rebleeding – Reduction in portal-pressure gradient | – Restricted expertise – Hepatic encephalopathy – Hepatic decompensation – Acute right heart failure

|

| Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration | Interventional radiology | – Efficacious control of bleeding in patients where TIPSS is contraindicated | – Restricted expertise – Portal hypertensive complications – Portal/renal vein thrombosis |

Table 1: Summary of major therapeutic options for duodenal variceal therapy and their advantages and disadvantages. Abbreviations: EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; TIPSS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt.

Figure 1: (A) Covered duodenal varices on the posterior wall of the descending duodenum (black arrow). (B) Appearance after cyanoacrylate glue injection with area of ulceration at the variceal injection site. (C) Venous phase coronal imaging with contrast, showing decompensated liver cirrhosis with ascites (double headed white arrow) and duodenal varices draining into the right gonadal vein (white arrow). (D) Radiological appearances after cyanoacrylate and lopiodol injection sclerotherapy (white arrow).

Figure 2: Proposed management algorithm for portal hypertensive bleeding from duodenal varices. Abbreviations: ECI, endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; FBC, full blood count; G&S and CXM, blood group and screen and cross-match; U&E, urea and electrolytes; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; VBL, variceal band ligation.

Author Biographies

T H Tranah

Dr Deepak Joshi

Dr Shanika Nayagam

CME

SSG Digest This! Acute Decomposition of Liver Disease

10 July 2024

BSG Grand Rounds - Updates in the management of alcoholic hepatitis

27 June 2024

Managing alcohol-related hepatitis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

27 February 2024

1. Procopet B, Tantau M, Bureau C. Are there any alternative methods to hepatic venous pressure gradient in portal hypertension assessment? J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2013;22:73–78.

2. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Vascular diseases of the liver. J Hepatol 2016;64:179–202.

3. Stephen G, Miething R. Roentgendiagnostik varicoser duodenal-veranderungen bei portaler hypertension. Radiologie 1968;8:90.

4. Khouqeer F, Morrow C, Jordan P. Duodenal varices as a cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Surgery 1987;102:548–52.

5. Bhagani S, Winters C, Moreea S. Duodenal variceal bleed: an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleed and a difficult diagnosis to make. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:bcr2016218669..

6. Watanabe N, Toyonaga A, Kojima S, et al., Current status of ectopic varices in Japan: Results of a survey by the Japan Society for Portal Hypertension. Hepatol Res 2010;40:763–76.

7. Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut 2015;64:1680–704.

8. McPherson S, Dyson J, Austin A, Hudson M. Response to the NCEPOD report: development of a care bundle for patients admitted with decompensated cirrhosis-the first 24 h. Frontline Gastroenterol 2016;7:16–23.

9. Park SW, Cho E, Jun CH. Upper gastrointestinal ectopic variceal bleeding treated with various endoscopic modalities: case reports and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e5860.

10. Shiraishi M, Hiroyasu S, Higa T, Oshiro S, Muto Y. Successful management of ruptured duodenal varices by means of endoscopic variceal ligation: report of a case. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:255–57.

11. House T, Webb P, Baarson C. Massive hemorrhage from ectopic duodenal varices: importance of a multidisciplinary approach. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2017;11:36–41.

12. Yoshida Y, Imai Y, Nishikawa M. Successful endoscopic injection sclerotherapy with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate following the recurrence of bleeding soon after endoscopic ligation for ruptured duodenal varices. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:1227–29.

13. Sato T, Yamazaki K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ohmura T, Suga T. The value of the endoscopic therapies in the treatment of rectal varices: a retrospective comparison between injection sclerotherapy and band ligation. Hepatol Res 2006;34:250–55.

14. Liu Y, Yang J, Wang J, et al. Clinical characteristics and endoscopic treatment with cyanoacrylate injection in patients with duodenal varices. Scand J Gastroenterol 2009;44:1012–16.

15. Al-Hillawi L, Wong T, Tritto G, Berry PA. Pitfalls in histoacryl glue injection therapy for oesophageal, gastric and ectopic varices: a review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016;8:729–34.

16. Lee YT, Chan FK, Ng EK, et al. EUS-guided injection of cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc 2000;52:168–74.

17. Romero-Castro R, Ellrichmann M, Ortiz-Moyano C, et al. EUS-guided coil versus cyanoacrylate therapy for the treatment of gastric varices: a multicenter study (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2013;78:711–21.

18. Jonnalagadda SS, Quiason S, Smith OJ. Successful therapy of bleeding duodenal varices by TIPS after failure of sclerotherapy. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:272–74.

19. Almeida JR, Trevisan L, Guerrazzi F, et al. Bleeding duodenal varices successfully treated with TIPS. Dig Dis Sci 2006;51:1738–41.

20. Saad WE, Lippert A, Schwaner S, Al-Osaimi A, Sabri S, Saad N. Management of bleeding duodenal varices with combined tips decompression and trans-TIPS transvenous obliteration utilizing 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam sclerosis. J Clin Imaging Sci 2014;4:67.

21. Hashimoto R, Sofue K, Takeuchi Y, Shibamoto K, Arai Y. Successful balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for bleeding duodenal varices using cyanoacrylate. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:951–54.

22. Zamora CA, Sugimoto K, Tsurusaki M, et al. Endovascular obliteration of bleeding duodenal varices in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur Radiol 2006;16:73–79.

23. Wang CS, Jeng LB, Chen MF. Duodenal variceal bleeding--successfully treated by mesocaval shunt after failure of sclerotherapy. Hepatogastroenterology 1995;42:59–61.

24. Henderson JM, Yang Y. Is there still a role for surgery in bleeding portal hypertension? Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;2:246–47.

25. Rosch J, Keller FS. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: present status, comparison with endoscopic therapy and shunt surgery, and future prospectives. World J Surg 2001;25:337–45; discussion 345–46.