Author names: James Endersby and Dr Rami Sweis

Author institution: University College London Hospitals Trust

Introduction

The oesophagus is a complex muscular tube that transports food and fluid from the mouth to the stomach. It is bordered by the upper and lower oesophageal sphincters. Abnormalities of oesophageal motility can result in oesophageal symptoms including dysphagia, chest pain and regurgitation as bolus transport is disrupted and/or reflux inhibition is compromised. In the absence of infectious, inflammatory or malignant disease, and following failure of empirical therapy where reflux is suspected (e.g. acid suppressant medicines), guidelines recommend investigation of oesophageal function. The aim of this document is to review how non-malignant dysmotility can be investigated with high resolution manometry. Manometry methodology and parameters will be introduced, and motility disorder classification will be defined and put in clinical context. Even in the absence of dysphagia, if the aim is to test for reflux with ambulatory pH monitoring, manometry is required first as the pH sensor is routinely placed 5cm above the lower oesophageal sphincter.

Indications for patients with dysphagia

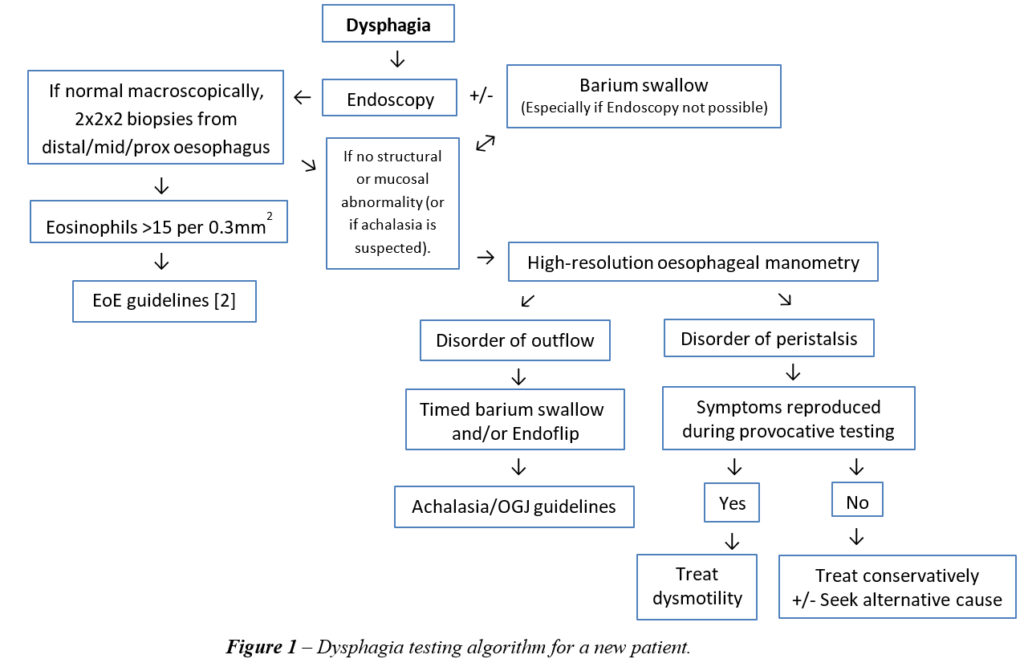

High resolution manometry (HRM) is the gold-standard test for the investigation of oesophageal motility disorders; however, it is important to consider the appropriate testing pathway for patients presenting with dysphagia prior to conducting HRM studies. Patients presenting with dysphagia can be categorised into 4 cohorts, those with:

- Structural abnormality (e.g. adenocarcinoma, stricture)

- Mucosal pathology (e.g. Eosinophilic oesophagitis (EoE))

- Motility disorder

- Hypervigilance/Hypersensitivity

Structural and mucosal pathology should be ruled out before investigating oesophageal function. This is undertaken primarily with endoscopy and should include oesophageal biopsies. A barium swallow might also be useful to appreciate more subtle structural abnormalities, particularly of the crico-pharynx [1]. High resolution manometry can then be considered to assess oesophageal function by investigating oesophageal body motility and lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) function. HRM utilises a multi-channel catheter to measure pressure within the full length of the oesophagus whilst swallowing, thus creating an intuitive display of oesophageal motility captured in real time. However, the final manometry report should always include results from all testing modalities; endoscopy, barium, etc.

A simple algorithm of how to investigate patients presenting with dysphagia is presented in Figure 1.

Oesophageal function

Manometry can provide visual representation of the tonic upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) and lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS). The proximal 1/3 of the oesophageal body is comprised of striated muscle, whilst the distal 2/3 is smooth muscle. With every swallow and opening of the UOS, the oesophageal body is inhibited, and the LOS relaxes (deglutitive inhibition), a nitric oxide mediated response. This is then followed by a cholinergic mediated excitation leading to coordinated peristalsis down the length of the oesophagus, thus propelling the swallowed bolus through the oesophagus, past the LOS and into the stomach. Abnormalities of oesophageal function commonly occur where the interplay between inhibition and excitation of the oesophageal body and sphincters are disrupted. To define normal and abnormal, manometry parameters have been established with validated normal ranges. Together, a classification of motility disorders has emerged, coined the Chicago Classification of motility disorders (currently in its 4th iteration) [3]. This provides a guide for the standard HRM testing protocol. The five common motility disorders are:

- Achalasia

- Oesophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (OGJOO)

- Distal oesophageal spasm

- Hypercontractile oesophagus

- Ineffective oesophageal motility

High resolution oesophageal manometry methodology and metrics

The standard HRM testing protocol begins with a resting period, followed by a series of 10 repetitions of 5ml water swallows that are performed in the upright and/or supine positions. This is then followed by the option of reproducing normal eating and drinking behaviour (also known as ‘provocative testing’) by drinking larger volumes of water from a cup or syringe and/or by providing solids such as single cubes of bread, a sandwich or a bowl of rice. Details regarding this methodology can be seen in the technical review that accompanies the latest iteration of the Chicago Classification of motility disorders [4].

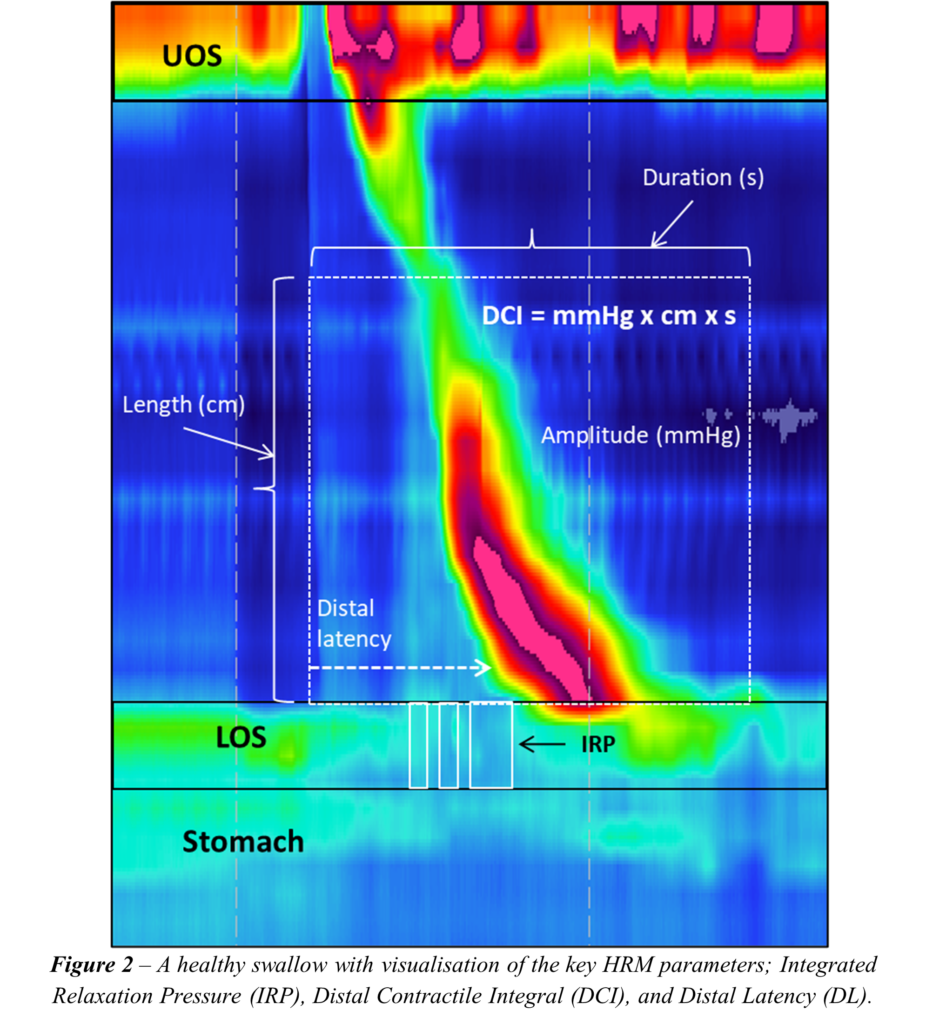

For every swallow, oesophageal body motility and LOS function is defined according to validated manometry parameters which are then averaged and compared to established normal values. Furthermore, recognised patterns of motility are described such that the final HRM report provides both an objective and subjective assessment of oesophageal function.

Manometry numerical metrics

Common HRM metrics that are used to define function and are routinely included in the standard report are presented. Note that these are used to describe oesophageal body and LOS function. Measurements of the UOS are currently less accurately defined with HRM in its present form and will not be covered in this overview; however new technologies with novel metrics are emerging that can better describe this highly moveable and complex structure.

- Integrated relaxation pressure (IRP)

IRP quantifies the degree of LOS relaxation. This metric has the highest sensitivity and specificity to identifying disorders of LOS obstruction such as achalasia [5].

- Distal contractile integral (DCI)

DCI is a measure of contractile vigour within the smooth muscle oesophagus. This incorporates three dimensions into one metric; the amplitude of pressure within the smooth muscle oesophagus, the duration of peristalsis, and the length of the smooth muscle segment. This parameter is established as the preferred measurement for describing hypotensive, hypercontractile and normal peristalsis.

- Distal latency (DL)

Spasm is not defined by the velocity of peristalsis, rather by the time taken to complete a swallow. As a minimum length of time is required for successful bolus transport from the oesophagus to the stomach, a short distal latency is suggestive of a premature contraction, in other words, a spasm.

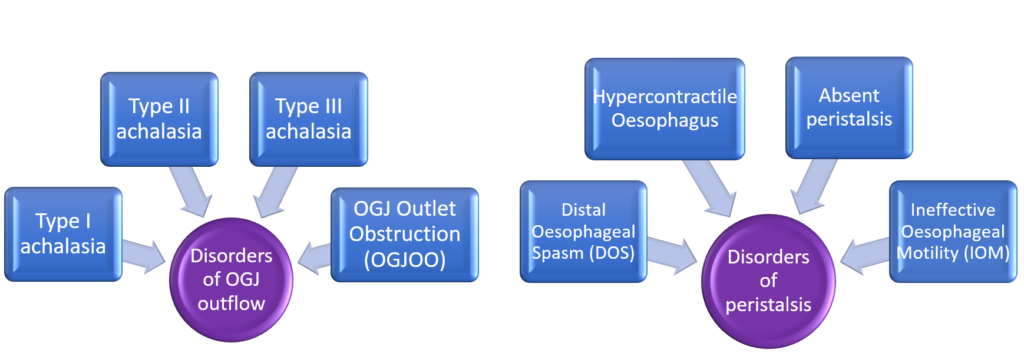

Classification of motility disorders

Disorders of motility are subdivided into those with problems arising from the OGJ or from the oesophageal body. A non-relaxing OGJ should always be excluded first as ultimately this will influence what transpires within the oesophageal body.

Figure 3 – Classification of motility disorders. Defining motility disorders should first define the presence or absence of OGJ obstruction, then describe disorders of the oesophageal body.

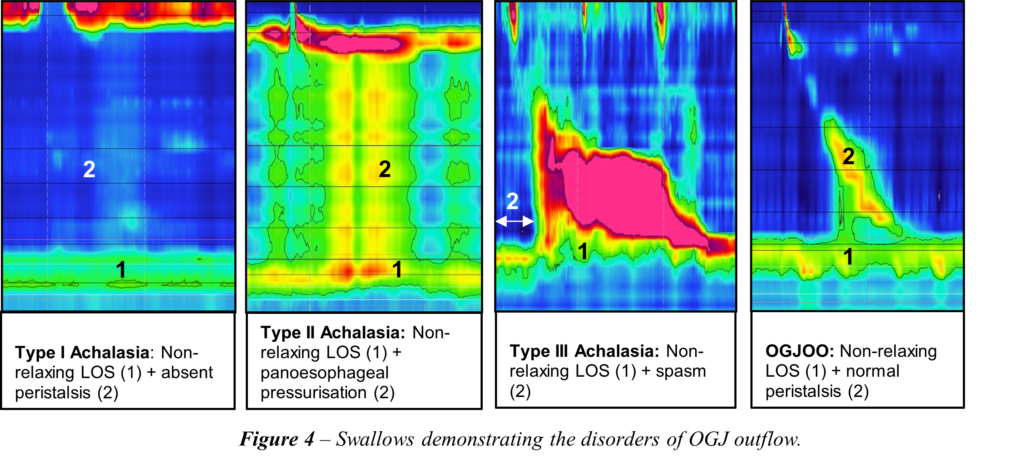

Disorders of OGJ outflow

The OGJ comprises the overlap of both the LOS and diaphragm, separation of which defines a hiatus hernia. Overlap of the two structures is seen in health and is defined as Type I OGJ morphology. In Type II OGJ morphology there is a 2cm separation and in Type III there is a greater than 2cm hiatus hernia. Where there is obstruction, provided that mechanical or mucosal abnormalities have been excluded (e.g. through endoscopy and barium), abnormalities of OGJ outflow are subtyped into manometrically-defined disorders:

- Achalasia type I: Non-relaxing LOS (raised IRP) with aperistalsis, with complete failure of any motility activity.

- Achalasia type II: Non-relaxing LOS (raised IRP) with a non-motile oesophageal body pressurisation (also known as pan-oesophageal pressurisation).

- Achalasia type III: Non-relaxing LOS (raised IRP) with concomitant evidence of spasm (reduced DL).

Oesophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (OGJOO): Non-relaxing LOS (raised IRP) but with normal oesophageal body function (e.g. no aperistalsis, pressurisation, hypercontractility or spasm).

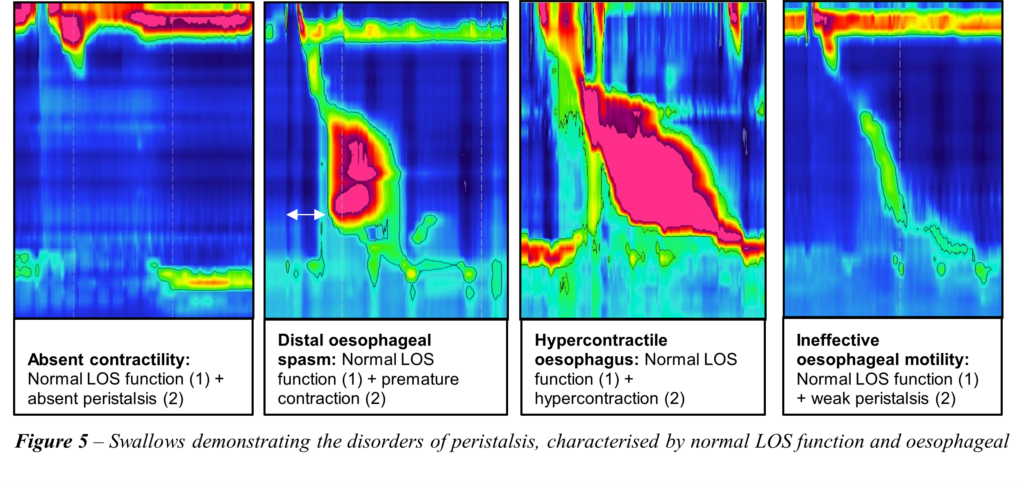

Disorders of peristalsis

Disorders of oesophageal body peristalsis range from those never seen in health (which are more likely to be associated with symptoms and interruption of bolus progression), to those that are just outside of the normal range and not necessarily associated with symptoms or interruption of bolus progress. In previous iterations of the Chicago Classification [6], these were subtyped as major and minor motor disorders respectively, terms that are still useful when describing disorders of motility.

Major Motor Disorders

- Absent contractility: 100% failed oesophageal peristalsis.

- Distal oesophageal spasm: Peristalsis associated with premature contractions/spasm (short DL).

- Hypercontractile oesophagus (also known as Jackhammer oesophagus): Motility associated with a markedly increased contractile vigour (raised DCI).

Minor Motor Disorders

Ineffective oesophageal motility: At least half of contractions either have a DCI that is below the lower limit of normal, or have frequent wide breaks in contraction, or where peristalsis alternates between normal and failed intermittently.

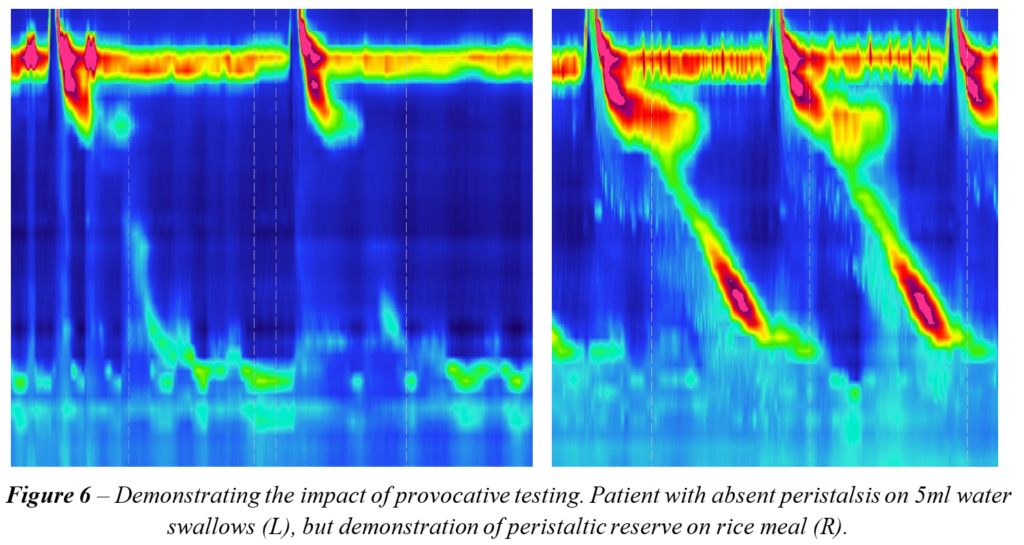

Provocative testing

Diagnoses should ideally be matched with reproduction of symptoms, which is possible when reproducing normal eating and drinking. Commonly, the small volume water swallow protocol is not sufficient to trigger symptoms or identifying the underlying dysmotility. Reproducing normal eating and drinking behaviour has inherent logic and has now been included into the routine protocol described in the latest iteration of the motility disorder classification. Also known as ‘provocative testing’, adding free drinking (rapid drink challenge; RDC), small volume water swallows in rapid succession (multiple rapid swallows; MRS), single solid swallows (e.g. cubes of buttered bread or similar) and/or a meal (e.g. bowl of rice or sandwich) have been undertaken with the aim of acquiring as much information as possible regarding the underlying culprit dysmotility. Provocative testing can also exclude hypotensive/ineffective motility that might have been seen during single water swallows, with the aim of confirming the presence of normal underlying motility when challenged, also known as ‘peristaltic reserve’.

Presentation and therapy

Patients with motility disorders can present with a variety of symptoms, ranging from mild to severe and debilitating, even with nutritional compromise. Presentation can be in the form of dysphagia with a sensation of food sticking or hold up, consequent chest pain, regurgitation of retained contents and/or weight loss. Treatment commonly targets dysmotility as it is identified on the HRM study. Where OGJ obstruction is the primary problem, treatments range from injecting botulinum toxin into the LOS muscle, to endoscopic dilatation, or transection of the LOS muscle itself either endoscopically or surgically. Oesophageal body dysmotility therapy ranges from considering a prokinetic where motility is poor, to medicines that reduce smooth muscle activity (e.g. calcium channel blockers or nitrates) where hypercontraction or spasm is the primary problem. Also, acid reducing therapy (e.g. proton pump inhibitors) can also be helpful as primary or adjunctive therapy as reflux might be the aetiology to the oesophageal body dysmotility. Psychological comorbidity should also be considered, particularly where symptoms have a prolonged and deleterious impact, especially when therapy is not possible or curative.

Key takeaway points

- Dysphagia should be investigated initially by an endoscopy with biopsies to rule out malignancy or other mucosal pathologies. Barium swallow can help define oesophageal structure and provide additional information with regards to function.

- HRM measures pressure throughout the length of the oesophagus and LOS in real time as the patient swallows.

- When classifying oesophageal motility, OGJ function should be addressed first before disorders of oesophageal body motility are described.

- The HRM study aims to reproduce normal swallowing behaviour. To improve diagnosis, allowing the patient to eat and drink as they would normally is more likely to illicit symptoms and, in turn, identify the culprit motility disorder.

Author Biographies

James Endersby

James Endersby

James Endersby qualified as a clinical scientist in the summer of 2021. He studied Bioengineering MEng for his undergraduate degree at the University of Sheffield, before completing the Scientist Training Programme at Nottingham University Hospitals Trust, specialising in clinical measurement and development. He is now unit lead of the GI Physiology Unit at UCLH, providing diagnostic tests for the assessment of oesophageal and anorectal function alongside supporting general service provision. In his spare time, he enjoys all things sport, with a particular love for football and golf.

Dr Rami Sweis

Dr Rami Sweis acquired his bachelor’s degree in 1994 from the University of Illinois at Chicago and his medical degree in 1999 from University of Edinburgh. He trained in gastroenterology at South East Thames and completed his PhD from Kings College London in 2012. He was appointed as Consultant in Upper GI Medicine and Physiology at UCLH in 2014 and is the Upper GI Physiology Lead. He also holds an Honorary Associate Professor position at University College London and the Fellowship for Higher Education.

He is an active member of the international High Resolution Manometry Working Group. He is also President of the Association of GI Physiologists (AGIP), a member of the Oesophageal section of the BSG and a founding member of the European Foregut Society.

Rami Sweis’ research is primarily focused on advancing the methodology and utility of the technology used to investigate reflux and swallowing disorders. He continues to publish and collaborate with fellow experts nationally and internationally. He recently co-authored the BSG Physiology guidelines, the ESGE endoscopic therapy guidelines and the newest iteration of the Chicago Classification of motility disorders.

Rami Sweis has a particular interest in investigating and managing complex benign as well as malignant/pre-malignant upper GI disorders, offering an array of endoscopic therapies including EMR, RFA, dilatation, TIF and POEM

CME

Masterclass: Achalasia - Beyond the Basics

05 November 2024

Barrett’s Surveillance – getting the basics right

29 July 2024

BSG Webinar: NHSE Evaluation of sponge capsule technology in Reflux

17 January 2024

[1] – Trudgill NJ, Sifrim D, Sweis R, et al. “British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for oesophageal manometry and oesophageal reflux monitoring”. Gut 2019 Oct;68(10):1731–1750.

[2] - Dhar A, Haboubi HN, Attwood SE, et al. “British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and British Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (BSPGHAN) joint consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults”, Gut 2022;71:1459-1487.

[3] - Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR, et al. Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0©. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2020;33:e14058.

[4] - Fox MR, Sweis R, Yadlapati R, et al. Chicago classification version 4.0© technical review: Update on standard high-resolution manometry protocol for the assessment of esophageal motility. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2021;33:e14120.

[5] - Ghosh SK , Pandolfino JE , Rice J , et al . “Impaired deglutitive EGJ relaxation in clinical esophageal manometry: a quantitative analysis of 400 patients and 75 controls”. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2007;293:G878–G885.

[6] - Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Gyawali CP, Roman S, Smout AJ, Pandolfino JE; “International High Resolution Manometry Working Group. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0”. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015 Feb;27(2):160-74.