Keywords

- Drug-induced liver injury

- Hepatotoxicity

- Adverse drug reaction

Learning points

- Drug-induced liver injury should be considered in any acute liver injury or jaundice without evidence of biliary obstruction.

- Liver biopsy and HLA genotyping can help clinical management by differentiating DILI from AIH and excluding DILI secondary to certain drugs.

- There is no high-quality evidence that supports empirical use of steroids to treat DILI unless in scenarios when auto-immune hepatitis cannot be excluded.

Introduction

- Idiosyncratic drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is an unpredictable type of liver injury following exposure to medication within the recommended dose which is distinctive from liver injury caused by drug overdosage, commonly caused by paracetamol overdose (POD).

- DILI usually occurs after a latency period ranges from few days to months post-exposure compared to a period from hours to days in liver injury due to overdose.

- Its estimated crude incidence ranges between 14-19 per 100,000 inhabitants, the annual incidence of DILI in a prospective population-based study in Europe was 19.1 (95%CI, 15.4 – 23.3) (1). Nonetheless, the incidence of DILI secondary to commonly used medications was significantly higher:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate (43 per 100,000; 95% CI 24 – 70)

- Nitrofurantoin (73 per 100,000; 95% CI 20 – 187)

- Infliximab (675 per 100,000; 95% CI 184 – 718)

- Azathioprine (752 per 100,000; 95% CI, 205 – 1914)

- Incidence may be higher in elderly; DILI incidence in those aged >70 receiving consecutive prescriptions of flucloxacillin is 110.57 per 100,000 (95% CI, 70.86–164.48).

- DILI is a common cause of emergency admissions with jaundice after excluding biliary pathology. Following a large national audit in the UK of 881 consecutive patients admitted with jaundice, where a biliary obstruction was ruled out by imaging, idiosyncratic DILI was the second most common cause of liver injury (15% of cases) after alcoholic liver disease (2).

- DILI can progress to acute liver failure (ALF) accounting to 7-15% of total ALF cases (3).

Case definitions and patterns of idiosyncratic DILI

Thresholds to define DILI were defined in 2011 as follows:

- More than or equal to five-fold elevation above the upper limit of normal (ULN) for ALT OR

- More than or equal to two-fold elevation for ALP after ruling out a bone pathology OR

- More than or equal to three-fold elevation in ALT and simultaneous elevation of bilirubin exceeding two-fold.

Patterns of DILI

The pattern of DILI is based on the earliest identified liver chemistry elevations above the upper limit of normality (ULN) that fit DILI criteria and defined using R-value where R = (ALT/ULN)/(ALP/ULN). There are three patterns of DILI:

- Hepatocellular (R ≥5); the most common drugs associated with this pattern of DILI are diclofenac, disulfiram, efavirenz, fenofibrate, isoniazid, lamotrigine, minocycline, nevirapine, nitrofurantoin, pyrazinamide, rifampicin and sulfonamide (4).

- Cholestatic (R ≤2) pattern is associated with DILI secondary to amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalosporins, chlorpromazine, erythromycin, flucloxacillin, penicillin, sulfonamide and terbinafine (4).

- Mixed (R >2 and <5) pattern is associated with drugs such as carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin and sulfonamides (4).

Severity of DILI

- The degree of elevation of liver enzymes does not accurately reflect the severity of the liver injury or predict clinical outcome. However, elevated conjugated bilirubin indicates an adverse prognosis. Mortality/ liver transplant rates exceed 10% in DILI patients with hepatocellular injury and jaundice (5, 6).

- The outcome is worse when acute liver failure develops in DILI than that in paracetamol overdose. Patients developing features of acute liver failure (jaundice, encephalopathy, ascites, and coagulopathy) should be referred urgently to a liver transplant centre.

Specific phenotypes of DILI

Drug-induced autoimmune hepatitis

- It is a clinically challenging phenotype that has been described following exposure to certain medications (nitrofurantoin and minocycline) after a long latency period of up to 2 years (4).

- It has also been described with α- methyldopa, diclofenac, herbal supplements, infliximab, adalimumab and statins. It is associated with biochemical and/or histological features that are indistinguishable from AIH, including the presence of anti-nuclear antibodies, hyper-gammaglobulinemia and interface hepatitis with plasma cells on histology.

Checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury

- Hepatitis secondary to checkpoint inhibitors has emerged as a distinctive entity following the remarkable expansion of the therapeutic role of checkpoint inhibitors as treatment for several malignancies.

- Its incidence varies according to the treatment regimen. In patients with advanced melanoma, ALT elevation ≥ 5-fold ULN was reported in 1% of patients treated with programmed cell death 1 inhibitor (anti-PD-1) monotherapy, 2% of patients treated with cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 inhibitor (anti-CTLA-4), and 16% of patients who received a combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 (7).

- The pattern of liver injury is heterogeneous, with cholestatic liver injury being the least common.

- Histological characteristics of checkpoint-inhibitor-liver injury are different from DILI of other drugs and AIH and include granulomas and central endotheliitis (caused by anti-CTL A-4 therapy) or lobular hepatitis (caused by anti- PD-1 or anti P.D.- L1 therapy) (4).

Stepwise approach to clinical diagnosis of DILI

- DILI can mimic any acute or chronic liver injury, and the first step of diagnosis is the physician’s clinical suspicion in any liver injury following exposure to prescribed medication or over the counter medications, including herbal and dietary supplements.

- Determining the onset of liver injury after exposure (latency), course of reaction after withholding medication (de-challenge), recurrence on re-exposure (rechallenge), time to resolution and knowledge about the hepatotoxic potentials of the suspected drug are crucial to establishing a temporal relationship with the suspected agent.

- Time to onset of DILI differ significantly between drugs; although most DILI cases occur within 3 months of exposure to a drug, apparent clinical DILI can arise following a prolonged period of drug exposure or after cessation of the drugs as with amoxicillin-clavulanate and flucloxacillin (4).

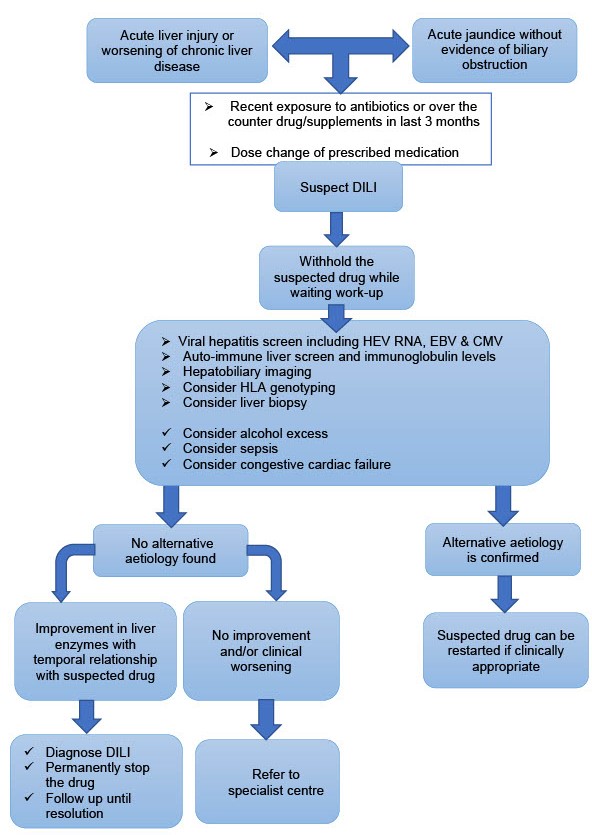

- The exclusion of alternative diagnoses is crucial, as illustrated in the proposed algorithm, (Figure 3). Every patient with suspected DILI should have abdominal imaging to rule out biliary obstruction or focal lesions, a virology screen including hepatitis E (HEV RNA), EBV and CMV and an autoimmune screen. In patients with cancer or who are immunosuppressed, viral PCR need to be considered.

Role of liver biopsy

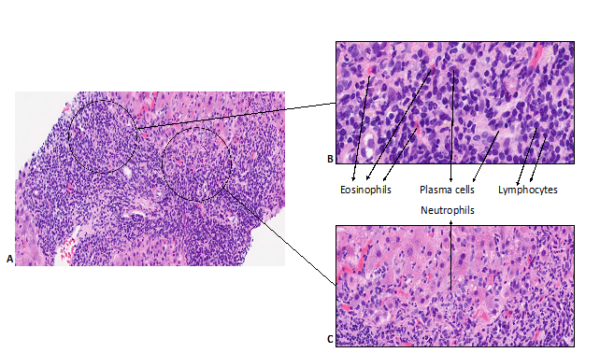

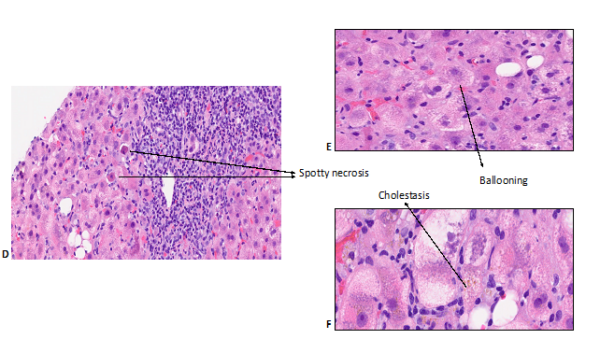

DILI can cause any pattern of liver pathology, although certain histological features are particularly suggestive of drug-induced aetiology. An evaluation of histological characteristics of idiopathic AIH and DILI revealed that eosinophilic infiltration, which is usually regarded as a feature of drug reaction, was not useful to differentiate both aetiologies and was more prominent in AIH (8). In fact, the presence of canalicular cholestasis favoured DILI in all patterns of liver injuries whereas rosette formation, portal plasma cells, severe portal inflammation and the presence of fibrosis favoured AIH. Moreover, some histological characteristics have been associated with clinical severity. The degree of necrosis, fibrosis stage, microvesicular steatosis, panacinar steatosis, cholangiolar cholestasis, ductular reaction, neutrophils, and portal venopathy were all associated with the severity of DILI whereas the presence of granulomas and eosinophils were more likely to be present in milder cases (9). Figures 1 & 2 illustrates portal and lobular changes in severe hepatocellular DILI secondary to Zanubrutinib (10).

Figure 1. Histopathological changes of portal tracts in zanubritinib-induced liver injury (10).

A: Prominent portal and interface inflammation; B: High-power imaging showing inflamed portal tracts with lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. C: Inflammation at the interface with neutrophil infiltration.

Figure 2. Histopathological changes of liver lobules in zanubritinib-induced liver injury (10). Lobular inflammation with spotty necrosis (D), ballooning (E) and cholestasis (F).

Hence, the benefits of a liver biopsy should be weighed against the risks and its limitations. Liver biopsy is justified when:

- Autoimmune hepatitis is one of the differential diagnoses in consideration

- Incomplete or no biochemical resolution after discontinuation of the drug

- Atypical clinical/laboratory features

- Liver injury related to checkpoint inhibitors

Role of pharmacogenetic testing

- Performance characteristics of HLA alleles as a diagnostic test in patients with DILI are comparable to those of autoantibodies and immunoglobulin profiles that are routinely performed in clinical practice for cases with acute liver injury(11).

- Pharmacogenetic testing might be helpful in the following clinical scenarios:

- HLA- DRB1*0301 or DRB1*0401 could be an adjunct in the differential diagnosis of DILI versus AIH; international AIH diagnostic criteria attributes additional scores for carriage of one of these alleles.

- HLA-B*5701 allele increases the risk of DILI following exposure to flucloxacillin 80-fold. 85% of those who develop flucloxacillin-induced DILI carry HLA-B*5701 compared to 6% of the general population. In clinical practice, this can be used to support the diagnosis as well as to rule out flucloxacillin-induced DILI with a negative predive value over 95% in challenging cases where DILI is one of the differential diagnoses (3).

- HLA-DRB1*1501 can help the clinical management of acute liver injury cases with recent exposure to amoxicillin/clavulanate to differentiate DILI from seronegative hepatitis by providing supportive (though not conclusive) evidence for the diagnosis of DILI.

Management

- The most critical step is timely recognition of liver injury and withdrawal of the suspected drug. In most cases, DILI improves after the withdrawal of the culprit drug.

- Empirical treatment with corticosteroids is not advisable, except when DILI with autoimmune features can’t be confidently differentiated from AIH. Checkpoint inhibitor-induced liver injury has been widely treated with steroids. This is based on the obvious assumption that immune mechanisms underlie its pathogenesis. However, there is emerging evidence that indicates that the liver injury in subgroups of these patients resolves without immunosuppression. On the other hand, there is no high-quality evidence to support a specific dose or regimen of immunosuppression so far (7).

- In the event that steroids are initiated when distinction between DILI and AIH is unclear, withdrawing immunosuppression once the injury completely resolves should be considered. Seventy percent or more of patients with idiopathic AIH relapse over the 4-year follow up without immunosuppression (12).

- Rechallenge of medications adjudicated as causative agent is not recommended, with 30% of cases developing recurrent DILI, which is associated with jaundice in 64%, hospitalization in 52% and deaths in 13% of cases (13). However, in certain cases, such as with the first-line anti-tuberculosis treatment regime, reintroduction of drugs after DILI has resolved are justified as the benefits of re-introduction outweigh the risks (3).

- Figure 3. Proposed algorithm to suspect, diagnose and manage idiosyncratic drug- induced liver injury (DILI).

Author Biographies

Dr Edmond Atallah

Dr Edmond Atallah is currently a Clinical Research Fellow at Nottingham University Hospitals. He is an NIHR clinical academic fellow and a senior Gastroenterology & Hepatology trainee at East Midlands denary. He is currently out of programme undertaking research, as part of his PhD, in drug-induced liver injury.

Professor Guruprasad P. Aithal

Professor Guruprasad P. Aithal graduated with MBBS from Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, MD (Internal Medicine) from Bangalore Medical College, Bengaluru, India, and completed his specialist training Gastroenterology in the Northern Deanery, U.K. He received PhD from the University of Newcastle and completed a fellowship at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, USA.

He is Professor of Hepatology and the Gastrointestinal & Liver Disorder Theme Lead for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre at the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust and the University of Nottingham.

He is the Deputy Project Co-ordinator and work package lead of the ‘Translational Safety Biomarker Pipeline (TransBioLine)’ programme of the Innovation Medicines Initiative (IMI) of the European Union (2019-24).

CME

SSG Digest This! Acute Decomposition of Liver Disease

10 July 2024

BSG Grand Rounds - Updates in the management of alcoholic hepatitis

27 June 2024

Managing alcohol-related hepatitis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

27 February 2024

- Björnsson E, Bergmann O, Björnsson H, Kvaran R, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug‐induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology [Internet]. 2013; 144:[1419-25 pp.].

- Donaghy L, Barry FJ, Hunter JG, Stableforth W, Murray IA, Palmer J, et al. Clinical and laboratory features and natural history of seronegative hepatitis in a nontransplant centre. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25(10):1159-64.

- Aithal GP. Drug-induced liver injury. Medicine. 2015;43(10):590-3.

- Andrade RJ, Chalasani N, Björnsson ES, Suzuki A, Kullak-Ublick GA, Watkins PB, et al. Drug-induced liver injury. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019;5(1):58.

- Andrade RJ, Lucena MI, Fernandez MC, Pelaez G, Pachkoria K, Garcia-Ruiz E, et al. Drug-induced liver injury: an analysis of 461 incidences submitted to the Spanish registry over a 10-year period. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(2):512-21.

- Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, Lee W, Stolz A, Talwalkar J, et al. Features and Outcomes of 899 Patients With Drug-Induced Liver Injury: The DILIN Prospective Study. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1340-52 e7.

- De Martin E, Michot JM, Rosmorduc O, Guettier C, Samuel D. Liver toxicity as a limiting factor to the increasing use of immune checkpoint inhibitors. JHEP Rep. 2020;2(6):100170.

- Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Miquel R, Smyrk TC, Andrade RJ, et al. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2011;54(3):931-9.

- Kleiner DE, Chalasani NP, Lee WM, Fontana RJ, Bonkovsky HL, Watkins PB, et al. Hepatic histological findings in suspected drug-induced liver injury: systematic evaluation and clinical associations. Hepatology. 2014;59(2):661-70.

- Atallah E, Wijayasiri P, Cianci N, Abdullah K, Mukherjee A, Aithal GP. Zanubrutinib-induced liver injury: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterology. 2021;21(1):244.

- Kaliyaperumal K, Grove JI, Delahay RM, Griffiths WJH, Duckworth A, Aithal GP. Pharmacogenomics of drug-induced liver injury (DILI): Molecular biology to clinical applications. J Hepatol. 2018;69(4):948-57.

- Björnsson ES, Bergmann O, Jonasson JG, Grondal G, Gudbjornsson B, Olafsson S. Drug-Induced Autoimmune Hepatitis: Response to Corticosteroids and Lack of Relapse After Cessation of Steroids. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017;15(10):1635-6.

- Hunt CM. Mitochondrial and immunoallergic injury increase risk of positive drug rechallenge after drug-induced liver injury: a systematic review. Hepatology. 2010;52(6):2216-22.