Key learning points

- How to diagnose NAFLD and NASH

- How to risk-stratify patients with NAFLD and NASH

- Stage-dependent treatment of liver disease

Introduction

With the increasing obesity epidemic, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) has become more common, affecting about 20% of the population in developed countries. It is defined as the accumulation of fat in more than 5% of hepatocytes in the absence of significant alcohol consumption (defined as daily consumption of ≥ 30 g for men and ≥ 20 g for women) or any other secondary cause of hepatic steatosis [1]. In about one-fifth of patients, NAFLD progresses to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) which can ultimately lead to liver cirrhosis in a further fifth of NASH patients and subsequently lead to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2]. The combination of the high prevalence of NAFLD with comparatively low numbers of progressive and advanced cases ensures that resource allocation strategies are required to tailor patient care and restrict referral according to the actual need [1].

Investigations and management

Diagnostic measures

Patients with NAFLD often come to light after being investigated for non-specific symptoms or monitoring of other conditions [3] and establishing a diagnosis of NAFLD is relatively straightforward being based principally on an echobright liver on ultrasound in the absence of other causes. Recommended investigations for the diagnosis of NAFLD and NASH according to European guidelines are depicted in Table 1. Every patient with suspected NAFLD should undergo a comprehensive workup including assessment of alcohol intake, metabolic risk factors and secondary causes of liver steatosis and, if present, causes for elevated liver enzymes. If clinically indicated, workup should be widened to the evaluation of less common liver diseases [1].

Whilst European guidelines recommend that NAFLD should be looked for in patients with obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus or metabolic syndrome [1] other guideline recommendations conflict on this point and suggest that data for the cost-effectiveness of such screening/case-finding programmes are needed first [4]. Notably, normal routine liver blood tests do not rule out NASH as a significant percentage of patients presents without liver test abnormalities [5].

The more challenging diagnostic element is establishing the degree of inflammation and fibrosis, for which a range of non-invasive modalities have been established to reduce the need for routine liver biopsy for all patients with NAFLD. Guidelines agree that liver biopsy should be reserved for patients at high risk of advanced liver disease or with suspected concomitant secondary liver disease [1, 6].

Table 1: Protocol for a comprehensive evaluation of suspected NAFLD patients [1]

| Level | Variable | |

| Initial | 1. | Alcohol intake: <20 g/day (women), <30 g/d (men) |

| 2. | Personal and family history of diabetes, hypertension and CVD | |

| 3. | BMI, waist circumference, change in body weight | |

| 4. | Hepatitis B/Hepatitis C virus infection | |

| 5. | History of steatosis-associated drugs | |

| 6. | Liver enzymes (aspartate and alanine transaminases (γ-glutamyl-trans-peptidase)) | |

| 7. | Fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, OGTT, (fasting insulin [HOMA-IR]) | |

| 8. | Complete blood count | |

| 9. | Serum total and HDL-cholesterol, triacylglycerol, uric acid | |

| 10. | Ultrasonography (if suspected for raised liver enzymes) | |

| Extended* | 1. | Ferritin and transferrin saturation |

| 2. | Tests for coeliac and thyroid diseases, polycystic ovary syndrome | |

| 3. | Tests for rare liver diseases (Wilson, autoimmune disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency) | |

| *According to a priori probability or clinical evaluation | ||

Non-invasive staging and liver biopsy

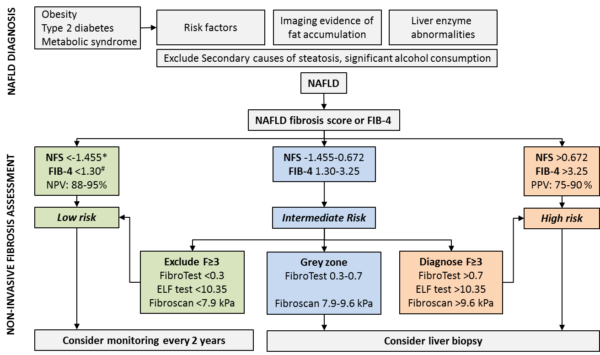

As outlined before, liver biopsy is not suitable as a tool for the initial assessment of disease severity and consequently, non-invasive measures and procedures have been developed to estimate the stage of the disease (algorithm see Figure 1).

Algorithms such as the NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) and Fibrosis 4 (FIB-4) are based on routine liver tests, anthropometric data and in the case of NFS on glycaemic status. Thus, they are easy to assess and suitable for primary care. Due to their high negative predictive value they can effectively rule out advanced fibrosis in the majority of patients, which can be managed in primary care. If clinically indicated, these tests can be repeated up to every two years [1]. Patients with intermediate risk should undergo second-line non-invasive testing either by additional tests like ELF test or FibroTest or by measuring liver stiffness [7, 8]. If advanced fibrosis is ruled out, patients can be treated as low risk and referred back to primary care.

If the non-invasive tests are not able to exclude advanced fibrosis, then a liver biopsy should be considered to determine degree of inflammation and fibrosis as well as rule out other concomitant liver diseases. The stage of liver fibrosis is the main determinant of prognosis and patients with stage 2 or more fibrosis should be considered for further follow-up and interventions [1, 9].

Stage-dependent therapeutic management

As NAFLD is tightly linked to weight and the metabolic syndrome, the mainstay of interventions is life-style change with diet and exercise to achieve weight loss of at least 7-10%. Likewise, cardiovascular risk factors should be assessed and treated according to respective guidelines [1]. As only a small proportion of patients are able to achieve weight loss goals on their own it might be warranted to include patients in structured weight-loss programmes to prevent further progression of the disease and hepatic decompensation. In selected, severely obese cases bariatric procedures may be considered [11].

As no licenced drugs for the treatment of NASH are available so far, guidelines recommend off-licence pharmacological treatment only in referral centres for patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis [1]. Guidelines make weak recommendations for Vitamin E and Pioglitazone [1, 6] and emerging data for patients with concomitant diabetes suggest that GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors may have positive effects on liver enzymes and liver histology [12] as well as cardiovascular mortality. New drugs are currently in Phase 2 and 3 trials and licensing of drugs for NASH can be expected for the near future.

For patients with end-stage liver disease the only curative treatment option is liver transplantation with outcomes comparable to other aetiologies of liver disease. When considering liver transplantation for NASH patients, special attention has to be put on assessment and management of cardiovascular comorbidities and obesity [13, 14].

Screening for hepatocellular carcinoma – who and when?

Due to the lack of systematic HCC surveillance programs for NASH patients, HCC is commonly diagnosed at a more advanced stage, often not suitable for effective cancer therapy [1]. Nevertheless, guidelines recommend surveillance for HCC in NASH only for patients who already developed cirrhosis although it is not cost-effective in non-cirrhotic NASH [1, 15] and hence is not recommended. Severe metabolic disease, positive family history and genetic factors like PNPLA3 rs738409 C>G polymorphism carrier status have been identified as additional risk factors for HCC development in non-cirrhotic NASH [16]. Thus, some experts believe HCC surveillance might be warranted in these patients at highest risk but more data are needed to make such a recommendation.

Conclusion

NAFLD and NASH are very frequent liver diseases with increasing prevalence. The diagnosis is based on patient history, clinical examination, the presence of liver steatosis, assessment of metabolic risk factors, liver biochemistry and for selected patients liver biopsy. Patients should undergo non-invasive assessment for liver fibrosis to tailor management for the individual patient. The vast majority of patients may be managed in the primary care setting while specialist referral is warranted in patients with increased risk for advanced disease or suspected concomitant secondary liver disease. Amidst the lack of approved drugs, life style interventions with the aim to lose weight and, in the case of end-stage disease, liver transplantation are the only available treatment options so far with new pharmacological compounds expectably being licenced in the near future. Surveillance for HCC is only recommended in NASH cirrhosis.

Author Biographies

Dr Paul Horn

Dr Paul Horn graduated from Friedrich Schiller University Jena, Germany, in 2015 and since then worked as a trainee in Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology at Jena University Hospital in the Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Infectious Diseases. In 2019 he joined the Centre for Gastrointestinal and Liver Research in Birmingham for a PhD project on fibrosis progression in NAFLD.

His clinical and scientific interests lie in the mechanisms of disease progression in NAFLD and the impact of systemic inflammation and sepsis on liver function, especially in pre-existing steatotic liver disease and decompensated liver cirrhosis.

Dr Philip Newsome

CME

SSG Digest This! Acute Decomposition of Liver Disease

10 July 2024

BSG Grand Rounds - Updates in the management of alcoholic hepatitis

27 June 2024

Managing alcohol-related hepatitis and alcohol-related cirrhosis

27 February 2024

- European Association for the Study of the L, European Association for the Study of D, European Association for the Study of O. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol 2016;64:1388-402.

- Diehl AM, Day C. Cause, Pathogenesis, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2063-72.

- Armstrong MJ, Houlihan DD, Bentham L, et al. Presence and severity of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a large prospective primary care cohort. J Hepatol 2012;56:234-40.

- Newsome PN, Cramb R, Davison SM, et al. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. Gut 2018;67:6-19.

- Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. Non-invasive diagnosis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. A critical appraisal. J Hepatol 2013;58:1007-19.

- Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;67:328-57.

- Eddowes PJ, Sasso M, Allison M, et al. Accuracy of FibroScan Controlled Attenuation Parameter and Liver Stiffness Measurement in Assessing Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2019;156:1717-30.

- Vilar-Gomez E, Chalasani N. Non-invasive assessment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Clinical prediction rules and blood-based biomarkers. J Hepatol 2018;68:305-15.

- Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005;41:1313-21.

- Boursier J, Guillaume M, Leroy V, et al. New sequential combinations of non-invasive fibrosis tests provide an accurate diagnosis of advanced fibrosis in NAFLD. J Hepatol 2019;71:389-96.

- Lassailly G, Caiazzo R, Buob D, et al. Bariatric Surgery Reduces Features of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Morbidly Obese Patients. Gastroenterology 2015;149:379-88; quiz e15-6.

- Townsend SA, Newsome PN. Review article: new treatments in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;46:494-507.

- Tsochatzis E, Coilly A, Nadalin S, et al. International Liver Transplantation Consensus Statement on End-stage Liver Disease Due to Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis and Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 2019;103:45-56.

- Haldar D, Kern B, Hodson J, et al. Outcomes of liver transplantation for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: A European Liver Transplant Registry study. J Hepatol 2019;71:313-22.

- Vogel A, Cervantes A, Chau I, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2018;29:iv238-iv55.

- Cholankeril G, Patel R, Khurana S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: Current knowledge and implications for management. World J Hepatol 2017;9:533-43.